Page One

Page Two

Page Three

Page Four

Page Five

Page Six

Massey Air Museum, 33541 Maryland Line Road, Massey, MD, 21650

Grassroots Aviation

Page One

Page Two

Page Three

Page Four

Page Five

Page Six

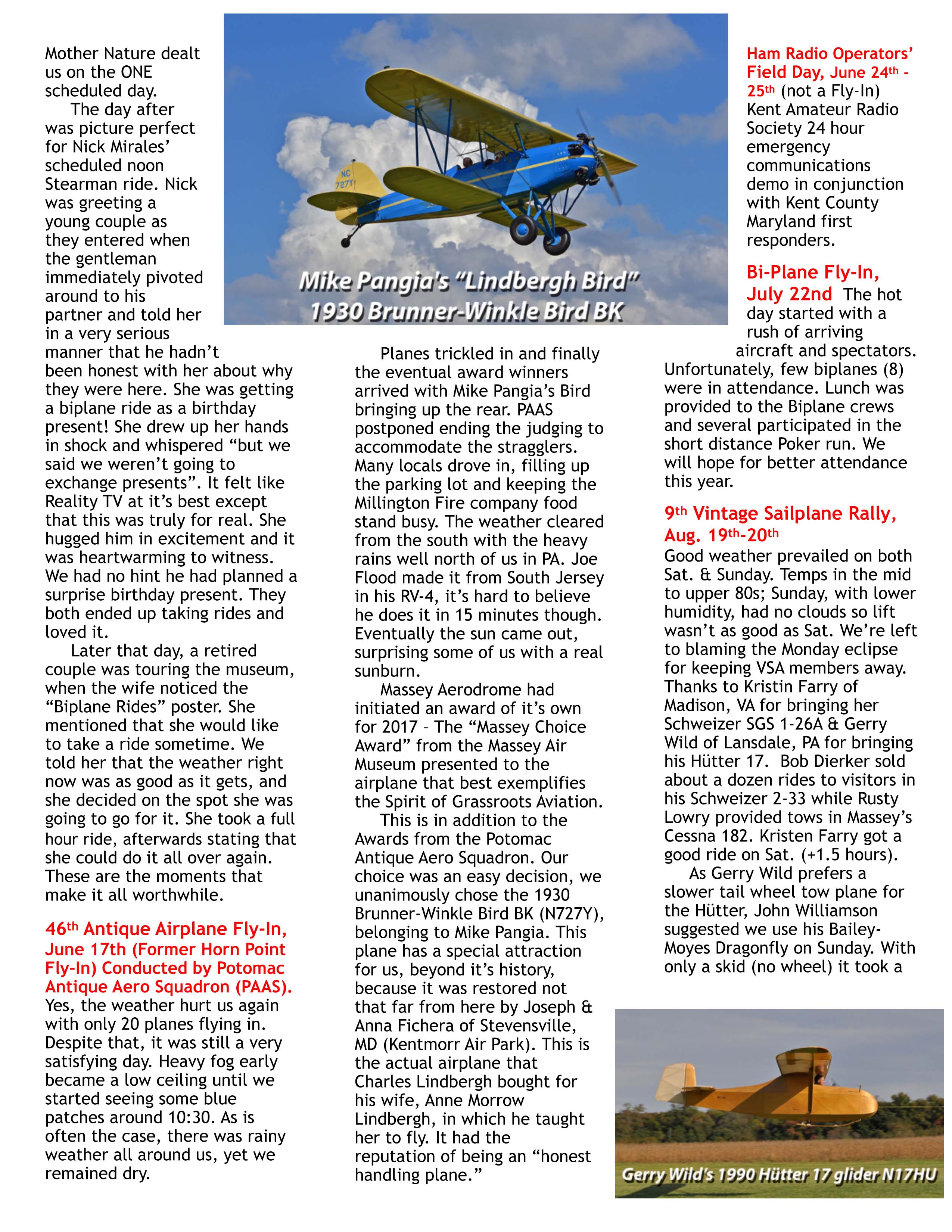

The Vintage Sailplane Rally enjoyed good weather for 2 of the 3 scheduled days (Aug. 17-19, 2018). We could have asked for more lift but considering the thunderstorms forecast (and around us) we were extremely fortunate to have sunshine on Friday & Saturday. Bob Dierker gave glider experience rides in his 2-33 to about a half dozen individuals, one of whom was a 91 year old veteran. Gerry Wild brought his unique Hütter 17 and Hans Hochradel flew is newly acquired Aviastroitel AC-5M Motor-Glider.

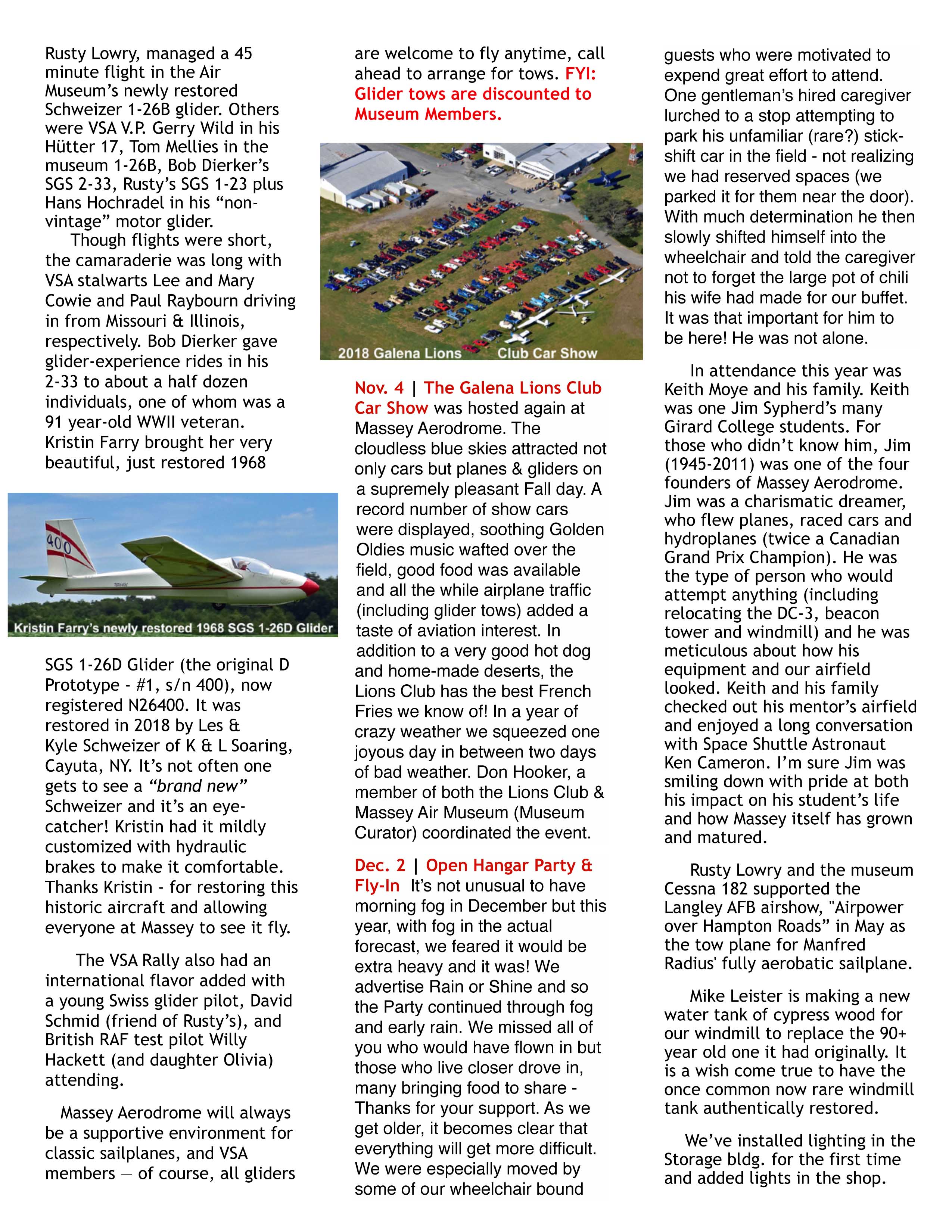

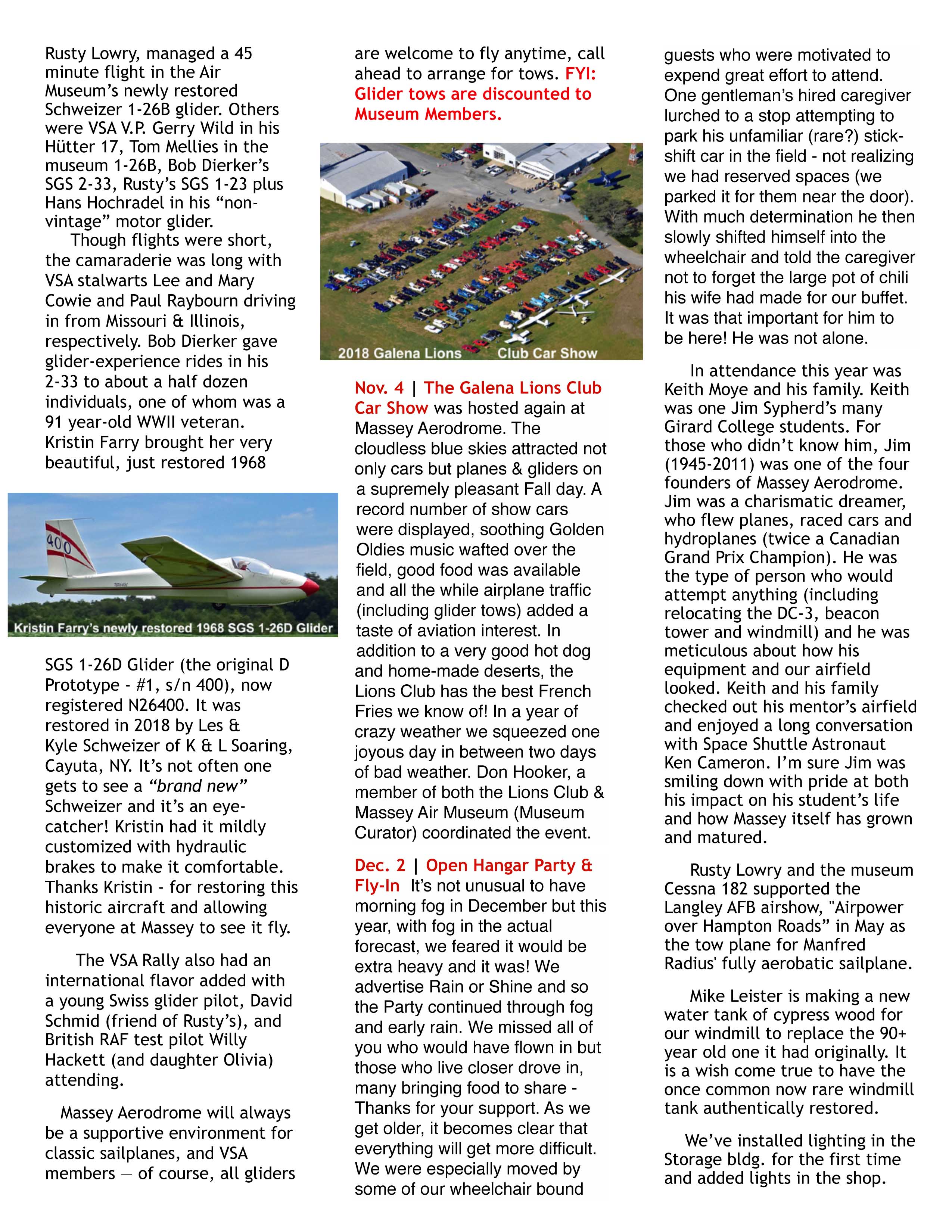

VSA regular, Kristin Farry brought her very beautiful, just restored 1968 SGS 1-26D Glider (the original #1 – D Prototype, s/n 400), now registered N26400. Restored in 2018 by K & L Soaring, Les & Kyle Schweizer of Cayuta, NY.

It’s not often one gets to see a “brand new” Schweizer and it’s an eye-catcher! Kristin had it mildly customized with hydraulic brakes and ??? to make it comfortable. Thanks Kristin – for restoring this historic aircraft and allowing everyone at Massey to see it fly.

Hans Hochradel, Annapolis, MD, got a tow from Rusty with the Massey C-182 but did not deploy the motor, grass is probably not conducive to self launching but should be useful for sustainment. The Aviastroitel is a Russian mid-wing, single seat, T-tailed motor glider (and unmanned aerial vehicle) that was produced by Aviastroitel, now Glider Air Craft. Engine is a 25 hp Zanzottera MZ-35R with 2-bladed retractable propellers. Wingspan: 41’ – 4”, Length: 17’ – 5”, Gross weight: 661 lb., Glide ratio: 35:1.

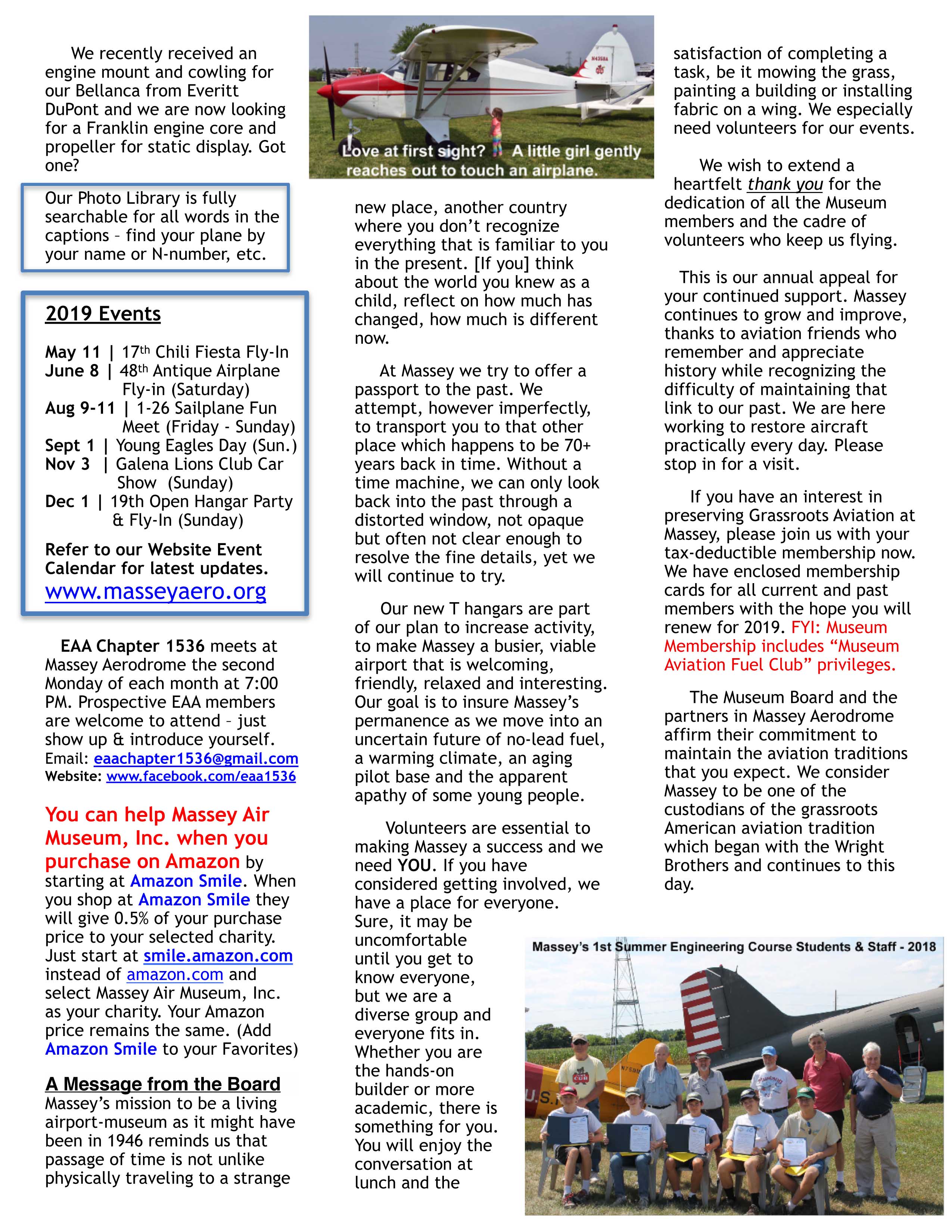

Tom Mellies flew the Massey Air Museum’s 1968 Schweizer SGS 1-26B, N5777S, s/n #393 that he helped to restore. It’s satisfying when all your work pays off with a good flying machine. We have a 1-26 open “sport canopy” that Tom is anxious to try out on it.

We tow Gerry Wild’s 1990 Hütter 17 (N17HU) with John Williamson’s Moyes Dragonfly (hang glider tug) because the 182 is really too fast. We’ve learned that a little soapy water on the grass helps to release the skid (no wheel), then the Dragonfly is the perfect tow plane. The Hütter is a 1934 Austrian design. Specifications: 143 lb. Empty wt., 348 lb. Gross Wt., 31.8’ Wing Span.

Gp. Capt. “Willy” Hackett, RAF, had been living in Arlington, VA, while posted to the UK’s F-35 Joint Program Office at PAX River when he discovered Massey’s Glider Rally three years ago and hasn’t missed it since. This year he brought his daughter, nine year old Olivia, who really enjoyed the day at the airport – and we enjoyed her company.

While nominally a Vintage Sailplane event, in actuality gliders of any age are invited, this is a relaxed opportunity to fly your glider and spend time with like-minded persons. Massey is open to all!

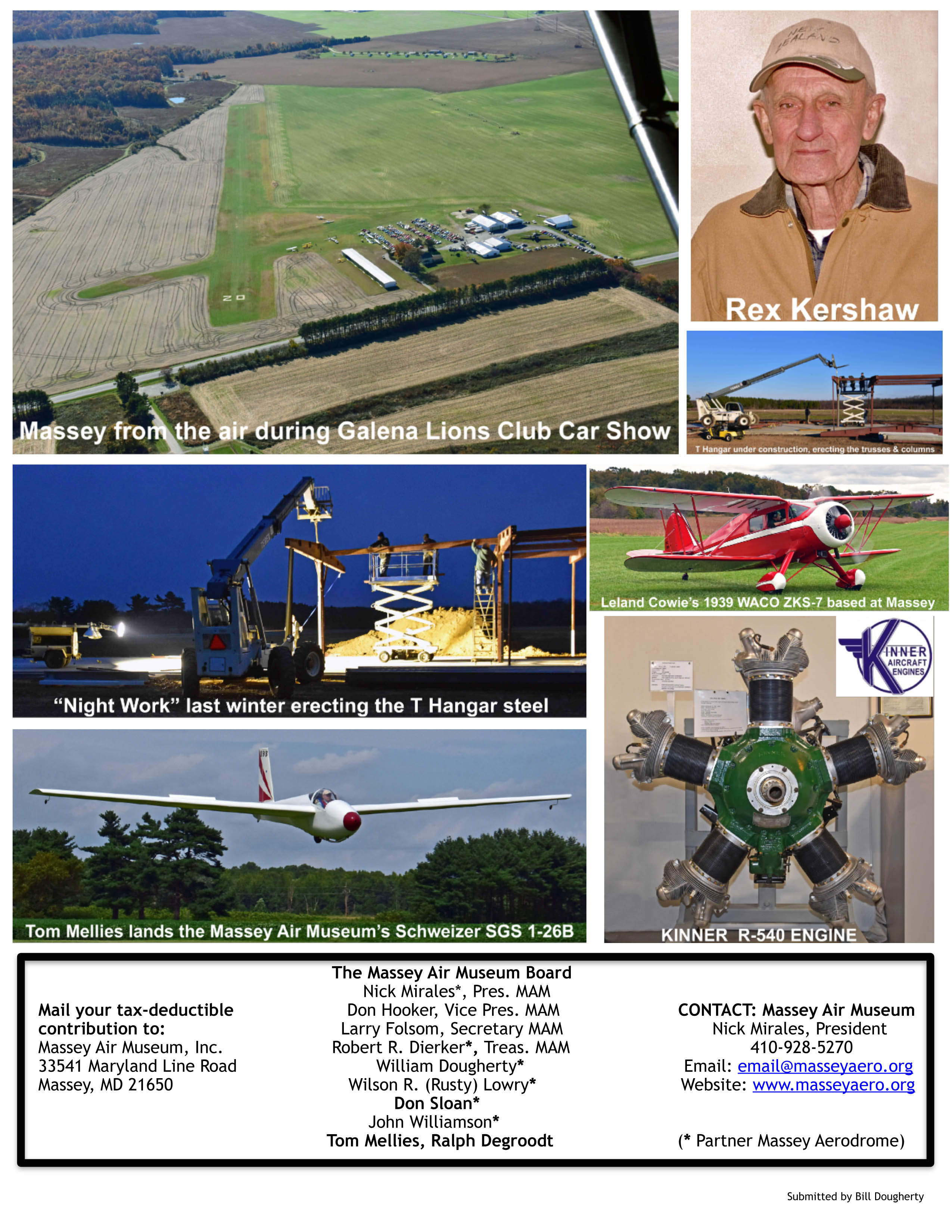

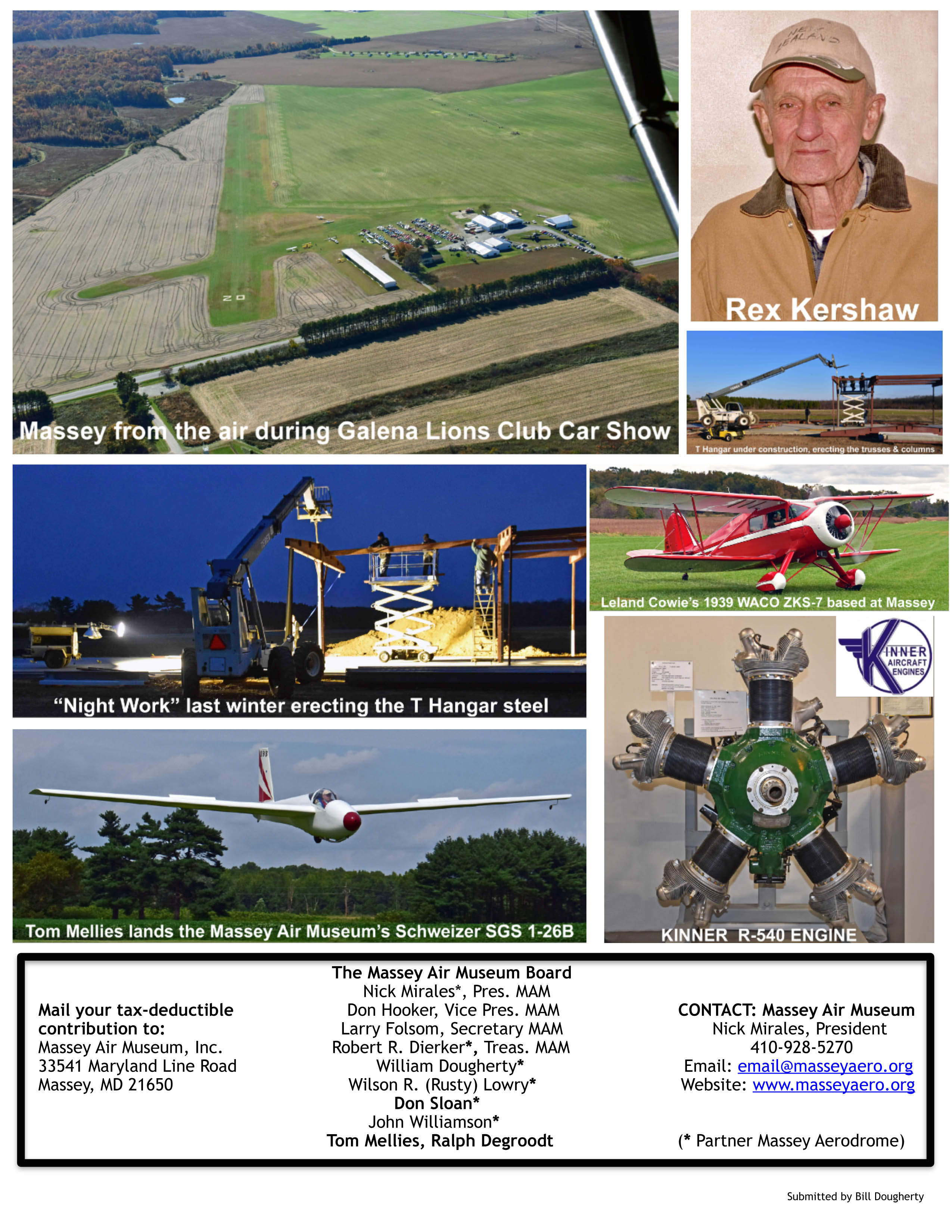

The 50th Anniversary & 47th Antique Airplane Fly-In held on June 9th, 2018, conducted by the Potomac Antique Aero Squadron (PAAS) chapter of the Antique Airplane Assoc. Hosted by Massey Aerodrome MD1. This is the only Antique Airplane Assoc. Judged event in our region (Formerly the Horn Point Fly-In). Thunderstorms were forecast for 2 PM and although there were scattered cells visible on radar around us, it did not rain at Massey until evening. The threatening weather held attendance to 39 guest aircraft (14 1st timers).

Retiring PAAS Fly-In Director, Mike Streiter, welcomed Gretta Thorwarth as the new Fly-In Director for 2019.

John Machamer of Gettysburg, PA received a bottle of Chandelle Winery Sonoma Sauvignon Blanc as the 2018 Massey “Choice” Award for his one of a kind 1930 DAVIS D-1K as well as the Grand Champion Antique Aircraft Award.

John Machamer of Gettysburg, PA received a bottle of Chandelle Winery Sonoma Sauvignon Blanc as the 2018 Massey “Choice” Award for his one of a kind 1930 DAVIS D-1K as well as the Grand Champion Antique Aircraft Award.

2018 Awards:

Grand Champion Antique Aircraft Award: N158Y Davis D-1K , John Machamer, Gettysburg, PA.

Sweepstakes Antique Aircraft Ward: N28621, Luscombe 8C, Mark Webb Delmar, MD.

Grand Champion Classic Award: N2224M, Piper J3C-65, John Lewis, Mickleton, NJ.

Sweepstakes Classic Aircraft: N2168C, Cessna 195B, Brian McCay, Earlysville, VA.

Grand Champion Contemporary Aircraft: N9218D, Piper Tri-Pacer PA-22-160, Frank Vitellaro, Pennington, NJ.

Best Customized Aircraft Award: N1131J C.A.S.A. 1.131 (Spanish built Bücker 131 Jungmann), Greg Stringer, Egg Harbor Twp. NJ.

Best Custom-Built (experimental) Aircraft Award: N235RV, RV-3, Bruce Barrett, Pasadena, MD.

Potomac Antique Aero Squadron President’s Award: N2168C, Cessna 195B, Brian McCay, Earlysville, VA.

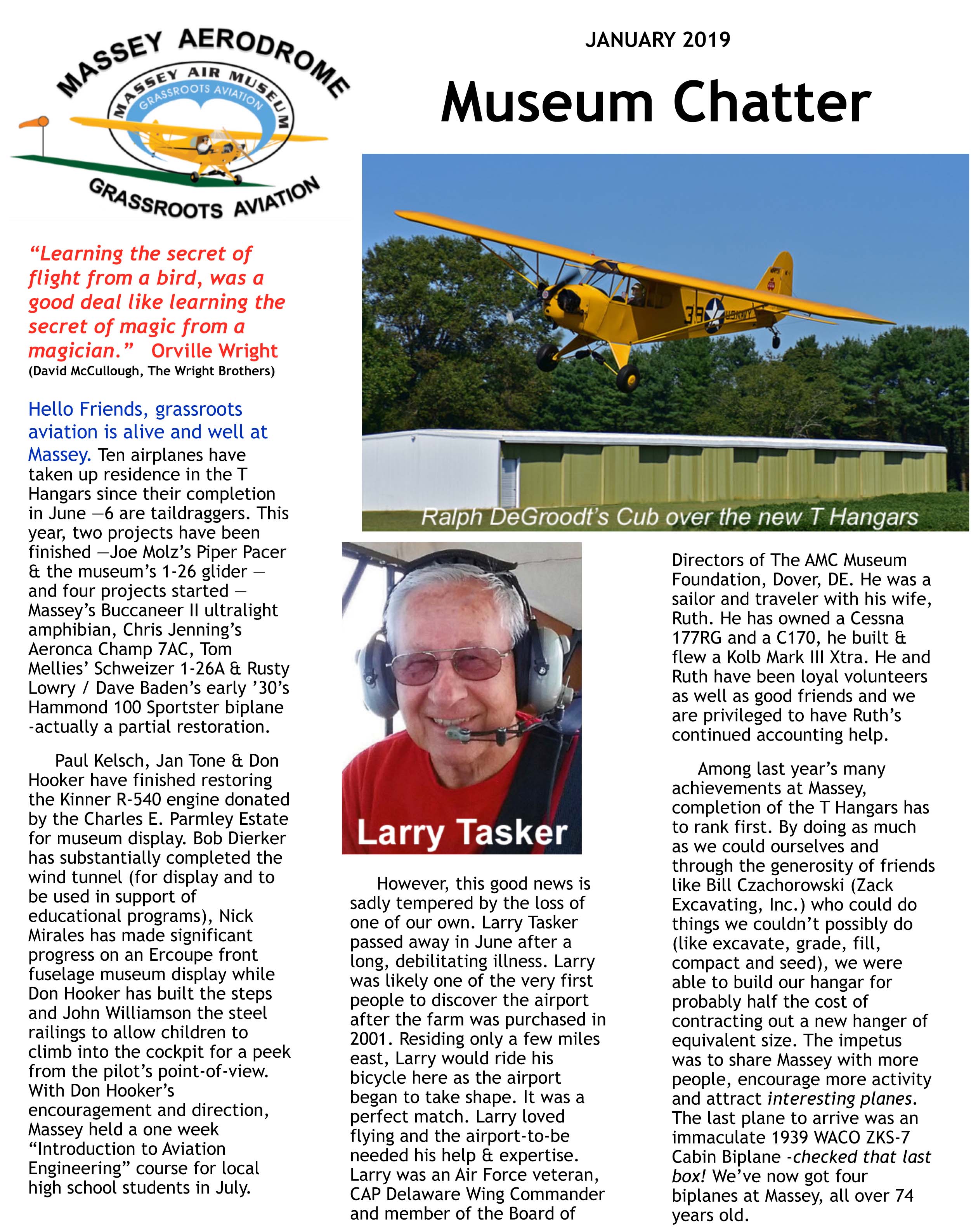

Antique Aircraft Assoc. Club Award: N24739 Piper J3 Cub, Ralph DeGroodt, Galena, MD.

Page One

Page Two

Page Three

Page Four

Page Five

Page Six

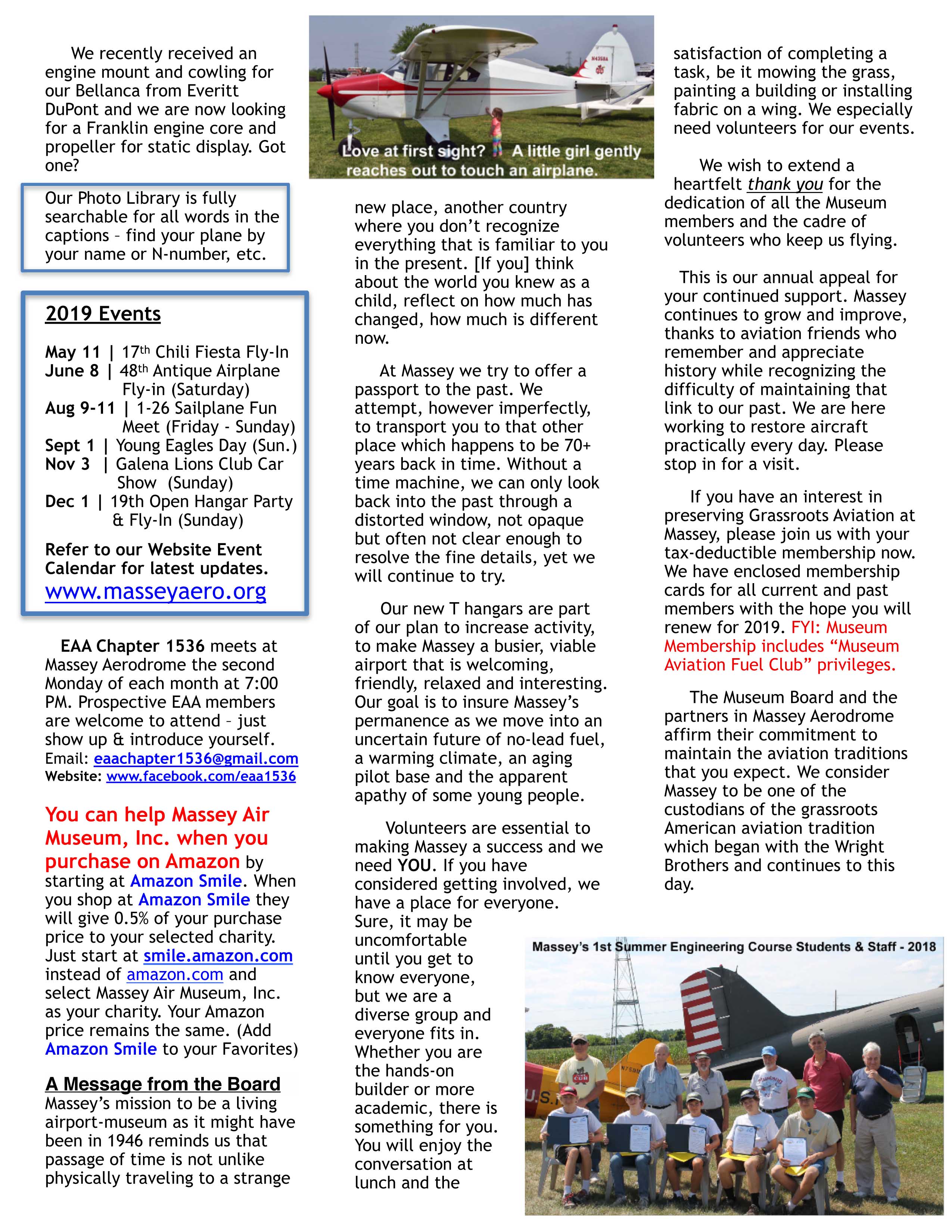

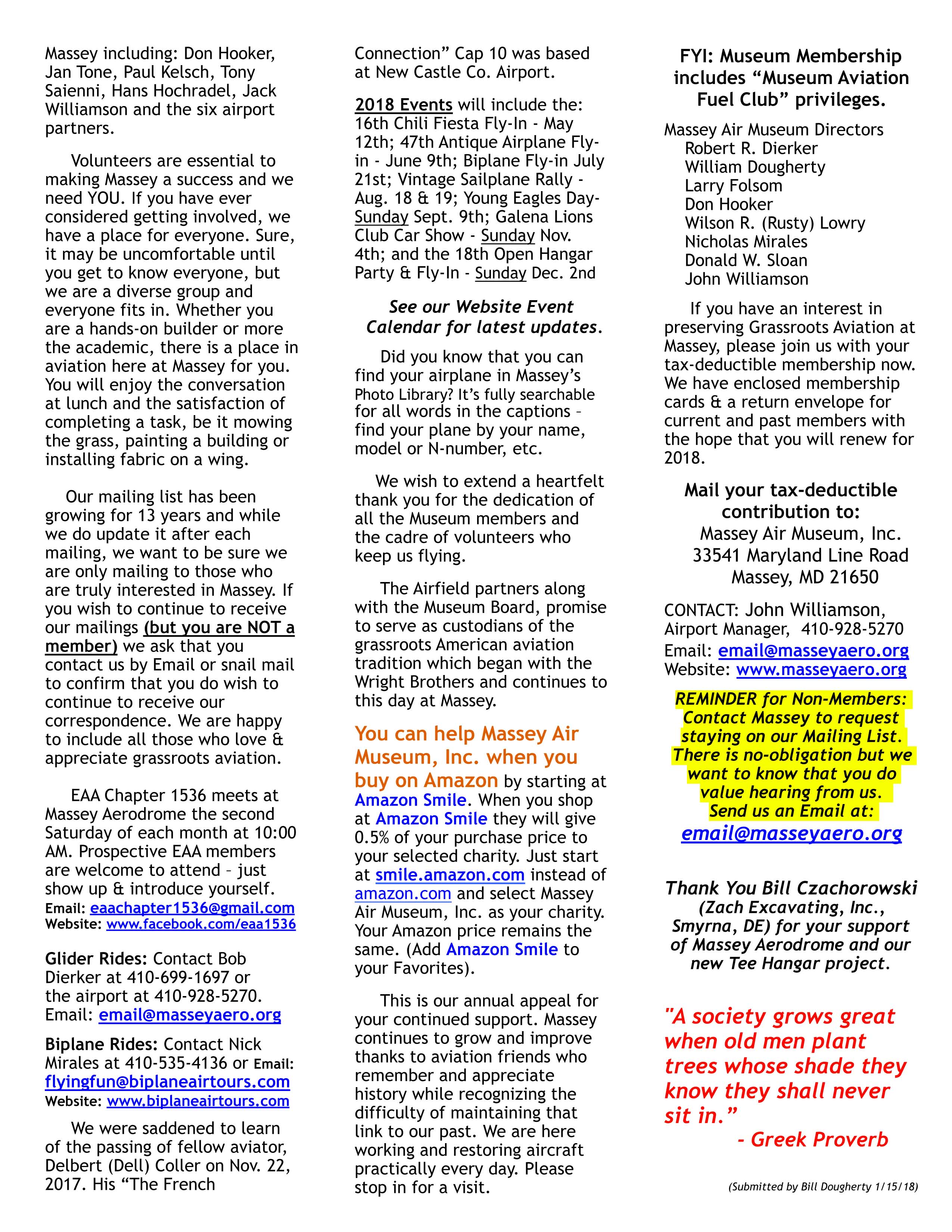

Massey’s 15th Chili Fiesta Fly-In (May 12, 2018) was a success despite low ceilings early and rain up north that kept most PA & NJ fliers at home. When the sun broke out we had 60 guest planes including a T-6 Texan (WWII trainer) from the Richmond, VA area. The parking lot was full of local drive-ins and our visitors brought just the right amount of chili to share. The turn-out made for a fine, relaxing day. The pilots come mainly for the camaraderie after a long Winter, a chance to look at some unusual, interesting planes and the free food is a bonus. Massey is fortunate to have such a well drained grass runway, and as usual it was perfect despite the rain earlier in the week. Massey built a ten unit T-Hangar over the Winter (our first) and it should be operational by July. When I say we built it, I mean that literally – Massey volunteers erected the structural steel frame and the 20 (20’) rolling steel doors. Now we are looking forward to the 50th Anniversary Antique Fly-In conducted by the Potomac Antique Aero Squadron (PAAS) on June 9th. This is the former Horn Point Fly-In that moved up to Massey 3 years ago. As the only Antique Airplane Assoc. (AAA) JUDGED event in our region, it attracts the best restorations and it feels like it belongs at Massey Aerodrome.

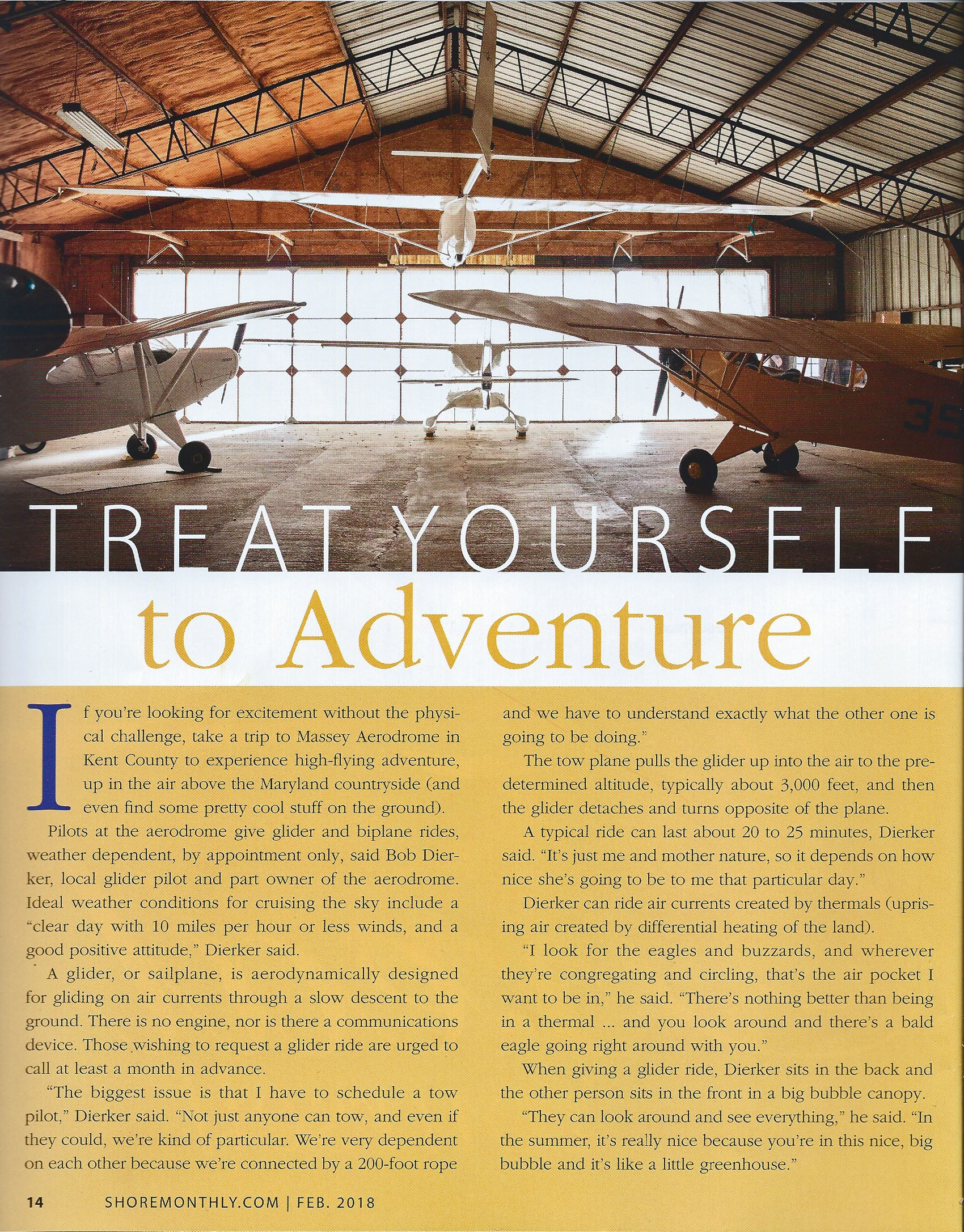

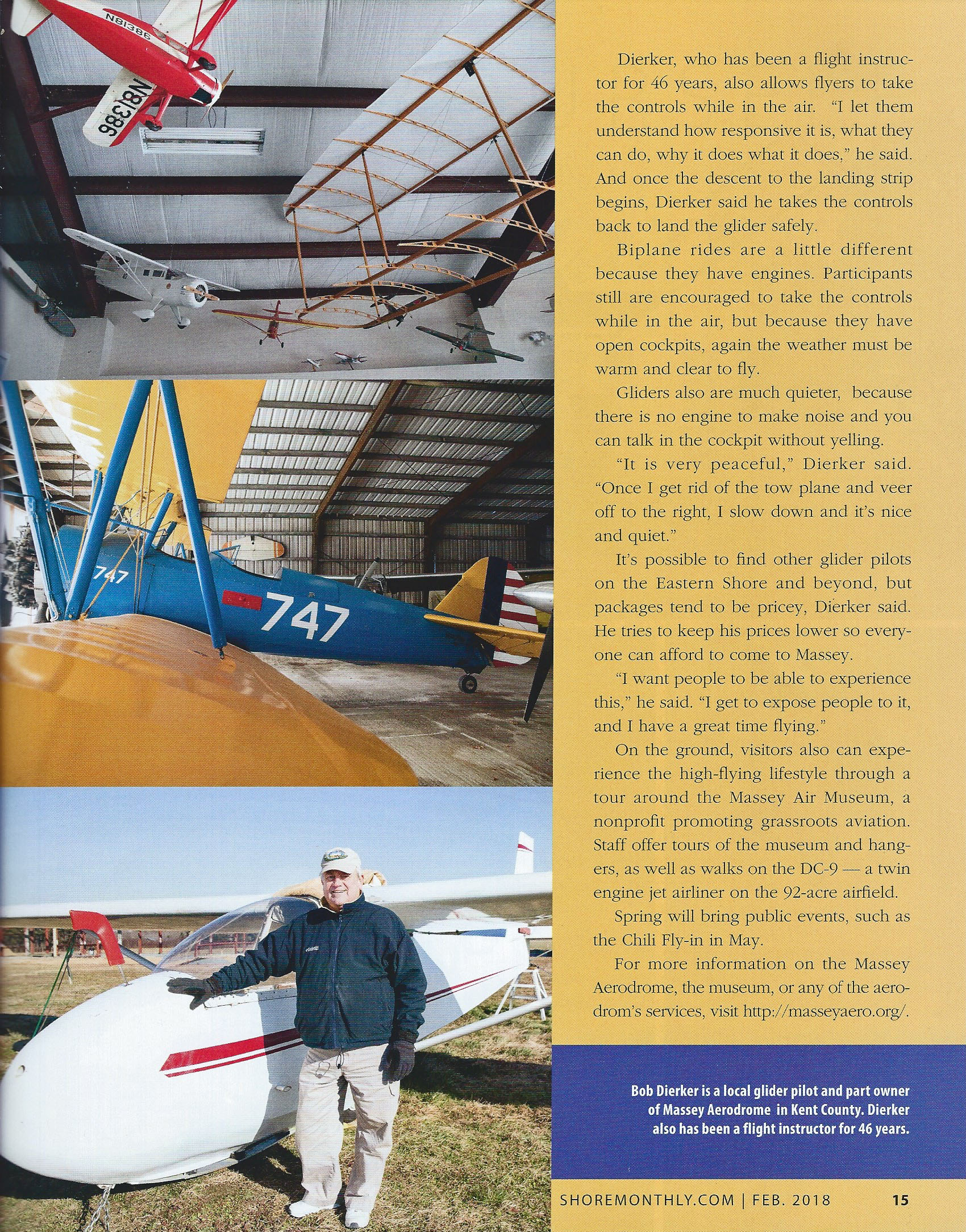

“TREAT YOURSELF to Adventure” suggests a visit to Massey Aerodrome to take a ride in a glider or a Biplane. Bob Dierker conducts the tour on a frigid December day – describing the joy of Soaring. Note a minor correction to the reporter’s narrative: We have a DC-3 twin piston engine airliner (1937) NOT a DC-9 twin engine jet airliner!

FIRST THINGS FIRST by Gill Robb Wilson

The boundary lamps were yellow blurs

Against the winter night

And I had checked the last ship in

And snapped the office light,

And paused a while to let the ghosts

Of bygone days and men

Roam down the skies of auld lang syne

As one will now and then …

When fancy set me company

A red checked lad to stand

With questions gleaming in his eyes,

A model in his hand.

He may have been your boy or mine,

I could not clearly see,

But there was no mistaking how

His eyes were questing me

For answers which all sons must have

Who builds their toys in play

But pow’r them in valiant dreams

And fly them far away;

So down I sat with him beside

There in the dim lit shed

And with the ghost of better men

To check on me, I said:

“I cannot tell you, sonny boy,

The future of this art,

But one thing I can show you, lad,

An old time pilot’s heart;

And you may judge what flight may give

Or hold in store for you

By knowing how true pilots feel

About the work they do;

And only he who dedicates

His life to some ideal

Becomes as one with the dreams

His future will reveal

Not one of whose wings are dust

Would call his bargain in,

Not one of us would welsh his part

To save his bloomin’ skin,

Not one would wish to walk again

Unless allowed to throw

His heart into the thing he loved

And go as he would go:

Not one would change for gold or pow’r

Nor fun nor love nor fame

The part he played and price he paid

In making the good game.

And of the living … none, not one

Regrets the scars he bears,

The sheer uncertainty of plans,

The poverty he shares,

Remitted price for one mistake

That checks a bright career,

The shattered hopes, the scant rewards,

The future never clear:

And of the living … none, not one

Who truly loves the sky

Would trade a hundred earth bound hours

For one that he could fly.

If that sleek model in your hand

Which you have brought to me

Most represents the thing you love,

The thing you want to be,

Then you will fill your curly head

With knowledge, fact and lore,

For there is no short cut which leads

To aviation’s door;

And only those whose zeal is proved

By patient toil and will

Shall ever have a part to play

Or have a place to fill.”

And suddenly the lad was gone

On wings I could not hear,

But from afar off came his voice

In studied tones and clear,

A prophet’s message simply told

For this is what he said

And why his hand will someday lead

Formations overhead,

“Who wants to fly has got to know:

Now two times two is four:

I’ve got to learn the first things first!”

.. I closed the hanger door.

BOB TUMPOLT’S Recollections of a flight engineer for TWA on the Lockheed Constellation (See transcript below from Ralph M. Pettersen’s Constellation Survivors Website. http://www.conniesurvivors.com/1-twa_flightengineer.htm

TRANSCRIPT of letter from Bob Trumpolt to Massey Aerodrome:

Robert H. Trumpolt, Canton, MI February 15, 2017

Hi everyone, My sincere compliments on your beautiful newsletter! The color photos really compliment the nice content. Your promotion of flying opportunities for youngsters is outstanding. I am a member of EAA Chapter 113 at Plymouth Mettetal Airport (1D2) in (Canton), MI. Like your organization, we promote all the same venues (homebuilts, Young Eagles and other groups flying events etc. Very active chapter. My visit to your beautiful facility on 10-20-2009, with 3 fullstops on that Lovely grass in a T-Craft (my first solo was in a T-Craft in 1950), seemed very appropriate for my last landing. Turns out, it was at the 2012 Piper Sentimental Journey (temp 100°!) that a kind gentleman allowed me to make my final Landing in his J-2 Taylor Cub (his had bad breaks!) what a way to end a 62 year flying career. The J-2 was 36 numbers younger than my J-2, which I owned as a 17 year old High School senior in 1952. (got my PPL in a Champ on Skis in ’52).

I enjoyed a Lunch with several of your members that day in 2009; when they found out I had been a TWA Connie flight engineer, it was fun relating adventures in the Ol’ girl.

Am now preparing a presentation of my training and “what it was like” on the Line with Connie. (see enclosed talk.) The entry level Connie F/E assignment went on to F/O and Capt. on the B-707, and Later F/O and Capt. on the L-1011. 27 years, 20 on Int’l.

Your dedication and hard work has created one of the finest aviation education facilities anywhere! Sincerely, Bob

____________________________________________

Email from RALPH PETTERSEN to Bill Dougherty of Massey Aerodrome:

Dec 15, 2017

RE: Bob Trumpholt’s Flight Engineer Article

Hope all is well. Bob’s story will be published in the February 2018 issue of Air Classics, which should hit the newsstands at the end of the month. I’ve also uploaded his story with some photos on my Connie Survivors website. Thanks very much for sending me his memoirs back in June. If not for you, the article would have never happened. Have a great Christmas holiday. Regards, Ralph Pettersen

(FYI: Aviation writer, Ralph M. Pettersen’s Website ConnieSurvivors.com is The authority on the Lockheed Constellation, he writes the Propliner Updates column (all propeller driven airliners) for Air Classics magazine and articles for Propliner, a respected aviation magazine from Great Britain.)

____________________________________________

Background: In Feb. (2017) Massey received the very complimentary letter (above) from Bob Trumpolt of Canton, Michigan. Bob had visited Massey way back in 2009 in his J-2 Taylorcraft and after receiving last year’s newsletter he was moved to write how much he had enjoyed his brief visit 8 years ago. He also enclosed copies of a hand-written 16 page manuscript of his recollections as one of the last TWA Flight Engineers on the Lockheed Constellation in the 1960’s with the note: “If you think it is an interesting piece for your members, feel free to pass it around – hope you get a chuckle or two out of it…”

It was so entertaining that we thought it deserved a wider audience so we contacted Ralph Pettersen who agreed and arranged for it to be printed in Air Classics magazine Feb. 2018 issue. You may read it here (see below) or on Mr. Pettersen’s website: http://www.conniesurvivors.com/1-twa_flightengineer.htm.

=======================================================================

Ralph M. Pettersen’s Constellation Survivors Website http://www.conniesurvivors.com

Memoirs of a TWA Constellation Flight Engineer (Dec. 2017 – Jan. 2018)

As most readers probably know, Trans World Airlines (TWA) was the largest civilian operator of the Lockheed Constellation and flew a total of 146 on a worldwide network from 1945 to 1967. Massachusetts native Bob Trumpolt had a 27 year flying career with TWA before retiring in September 1991 as a L1011 captain. He started his career with the company in October 1964 when he reported to TWA headquarters in Kansas City for what was to be TWA’s final Constellation flight engineer class. At 30 years old, Bob was the “old guy” in the class and he had come up the hard way through general aviation doing flight instructing, charter work and whatever else needed to be done. TWA training was well known in the industry to be very tough and after 4 ½ months of intense training, Bob became a full-fledged flight engineer and went on to fly on the L749, L749A and L1049G model Constellations. Bob has a way with words and has written a fascinating memoir of the 2 ½ years he spent on the Constellation.

Bob Trumpolt – In His Own Words

I was so fortunate and honored, to have served my great airline, starting out as a 30 year old newbie flight engineer on the L749, L749A, and the fabulous L1049 G “Super Connie”. It was hard work involving minus 5°F/oh-dark-thirty pre-flights “sticking” six fuel tanks, a hydraulic tank and four oil tanks on frosty and slippery wings. Then, down the ladder to the wheel well bays, etc., etc. I loved it all. But first, I want to give you an overview of Connie’s history followed by how I got to fit into her life and times and finally the training regimen to qualify for what was, in my view, a quite unique crew position in a very special airplane.

A Kindler Gentler Era

Put yourself back in the 1950’s and 60’s; by late 1964, Connie was relegated to flying from the east coast throughout the Midwest from Boston to Kansas City and many cites in between. Four models were in service; the L749, L749A, that wonderful L1049G and the L1649A, which had been relegated to flying freight. The passengers were so nice – dad in a three piece suit, mother with a little hat and white gloves, children scrubbed and dressed in their Sunday best.

The cockpit door was unlocked and a flight attendant (stew) might bring a nervous businessman or a wide-eyed child up front for a visit. The captain would tailor his chat to each, sending the businessman back looking much happier having seen “up-front” and, of course the youngster enthralled with all the noise, lights, dials and excitement in the wheelhouse. It was a wonderful PR moment now long lost to history along with the romance of flying in Connie.

So What Was it Like for Our Pax?

Picture this – its night, the engines are brought up to takeoff power, a mighty roar and a yellow stream of fire reaches back from those big stacks. As the power is reduced for climb, the fires stream begins to crawl back into the stacks. Later, as power is further reduced for cruise, engine roar subsides, props are fine tuned to a smooth hum and the short flame pattern turns a pretty blue. Now it’s time for the approach to landing; flaps and landing gear are extended and power increased to a loud rumble with those mighty props digging in and suddenly a small blue flame leaps out in a long yellow trail of fire. Wow, a loud and visual display of “thunder and lightning” as Connie makes her final prep for landing. Every flight is a great adventure for our pax and me too.

So How Did I Get a Shot at That Coveted Job?

1948 – Age 13, joined CAP (ground school)

1950 – Age 15, line boy at Bolton, MA airport. “The International” golf course now occupies the airport site. It was home to twelve training aircraft, from Champs, T-Crafts, Cessna 140s and a Cessna T-50 “Bobcat.” It was a very busy GA airport, mostly training G.I. Bill students.

1950 – First solo in a T-Craft in December 1950, having received 5:30 dual. An hour in a Champ in May, two flights in October in a T-Craft and four flights in a T-Craft in November. This was my total compensation for 7 ½ months’ work at the airport.

Spring 1952 – Private Pilot license in a Champ on skis. As a 17 year old high school senior, I bought a 1936 J-2 Taylor Cub, single ignition, no brakes for $150 including a complete spare engine in a crate! Licensed it for $75. To prove how ancient I am, I received 32:35 in a Link trainer in the mid-1950’s.

1956 – First charter flight job over the winter of 1956-1957, flying 503 hours in exactly six months out of a small gravel strip in Connecticut ranging from the Canadian border to Pittsburg and Philly. Nasty weather. The boss says “deliver your fare or you’re done here.” Worked six days a week for $50 plus $1 per hour flying time. All flown in a Tri-Pacer. Flew executives, Great Horned Owls, scallops, machinery, you name it, I flew it!

1964 – By now I had spent 14 years of flight instructing, charter flying for a Beechcraft dealer and had also worked 7 ½ years as a CAA/FAA control tower operator in Cleveland, OH, New Bedford, MA, and Bradley Field, Windsor Locks, CT. Finally in the fall of 1964, I received a telegram from TWA and a one-way airline ticket to report on October 26 for two days at Downtown Kansas City Airport for medical/psychological testing (no giggles please).

October 28, 1964 – “Welcome to the last class of Connie engineers.” A groan from the 15 military guys in my class of 18; they had just been released from military service due to McNamara’s base closures around the country. TWA was using the “dart board” method of setting up various pilot/flight engineer training – besides Connie flight engineer classes, classes were set up for B707, CV880 and B727 first officers, and jet flight engineers.

Thanks to a big feud going on between the Flight Engineers’ International Association (FEIA) and Airline Pilots Association (ALPA), a new cockpit position called “second officer” was mandated with the sole duties consisting of keeping the jet’s flight log and taking coffee orders. Those folks did not fare well at the end of their one year probationary period when they were put in the simulator and many did not make it. Other aspects of this fight, was the “old” mechanic flight engineers that were given a chance to obtain a commercial and an instrument rating at a training base on Long Island at company expense. These old timers would often say “all those pilots do is watch the autopilot and drink coffee, I’ve got a real job!” Well, we lost a bunch more when they were thrown in the little DC-9 simulator and never even got to the airplane before they were legally fired. Some of them became very competent captains later on but not many. On their probation period, first officers had one year where the union couldn’t help them; if you looked cross-eyed at a captain he could “turn you in.” Most unfairly, the probationary period for flight engineers was 1 ½ years, so more jeopardy plus no line pay for an extra six months. Flight engineers pay was $500 per month!

Study Buddies and Apartment Dwellers

Each guy teamed up with another to facilitate back and forth training after hours to drive all the minutia into our heads. As none of us had much money, we also had to pick roommates. So here’s how all that went down. Four of us gravitated towards each other and here’s the result: I, the “Yankee Bean” and almost thirty, the current cut-off for hiring, teamed up with the youngest of us four, Larry. Larry was the least qualified, coming from the rear seat of a B-47 bomber, where he was responsible for navigation, dropping bombs and electronic countermeasures. “How much actual flying did you get?” says I. “Once a month I got in the front seat, made three approaches and maybe two landings and that was it.” says he. Larry married an admiral’s daughter, but his family makeup was really strange; his Irish father played in a Dixieland jazz band in Puerto Rico and his Puerto Rican mother was an RN right there in Kansas City. Go figure! The remaining two roommates were highly qualified pilots. Bachelor Wayne had been a DC-3 captain for West Coast Airlines out in the Pacific Northwest and also a T-33 flight instructor in the USAF Reserves. Bachelor Gerry was a twin Beech flight instructor in the Royal Canadian Air Force. We went looking for a rental and found a two bedroom with 4 twin beds, a little kitchen and bathroom. It had to be situated downtown near the “stew zoo” which was a hotel TWA used exclusively for flight attendant trainees. Wayne would bring ladies back to our apartment for introductions and then off they went into the night while Larry and I sweated over our study materials late into the evening. For transportation to the training center, Larry drove in Wayne’s Corvette and I teamed up with Gerry in his VW. About the “Bug.” Gerry’s Beetle was light green, although you couldn’t really tell due to the accumulation of tar, mud and a general coating of crud. The interior was no better, with trash and dirt everywhere. After a few weeks of commuting in this little monster, I asked Gerry why all four fenders were crushed in and how about that big dent in the roof? He chuckled and said “well, when my instructor buddies heard I was resigning from the RCAF and going down to the states to fly for TWA, the boys decided to throw a party for me.” Down at the O-Club when everybody was well lubricated, someone said “Hey, Gerry’s car has to join the party!” With that, the beetle was rammed through the big O-Club doors smashing in all four fenders. “Then they grabbed me and slammed me down on the roof…that’s how the dent got there.” says he.

The Training

It was a very intensive 4 ½ month syllabus – it took Larry and I a 7 day a week, 10-12 hours per day of class and study time to absorb it all. No letup. A breakdown of the training: Formal ground school lasted seven very intensive weeks. 45:30 hours in a 1049G “procedures trainer” with 28:00 hours at the controls. The fellow I was paired with (he was an ex-controller from Anchorage, Alaska) was fired. The procedure was; we would each be asked a question in turn. It got so bad that the guy would stare at the panel and the instructor would snap his fingers, meaning “Bob, answer his question.” Double jeopardy! So I ended up with all the panel time and of course, all the questions. I couldn’t imagine that a guy with a wife and five kids could be so lazy. But there he was. An FAA check ride called “emergency review ride” finished the “simulator training” as TWA called it.

Next up, 7:00 hours of panel time in empty Connies (yay, the real thing finally!) plus 7:45 hours observer time, watching the other guy sweat, although it was frigid Kansas winter weather. Of course, another FAA check ride to get through this phase. A word about our check airman – John, working out of the MKC FAA office, bragged about TWA’s tough training course to his fellow inspectors. “You guys can check the other airlines, I only want to check TWA.” Well, you can imagine how that went over! John was no Santa Claus – he checked you to the standards that TWA demanded, which was a lot tougher than the Feds. (75% need to pass FAA written vs 85% for TWA, as an example) But, complete heresy reigned when after a check ride John would ask the captain for some panel time! A Fed touching the controls of an actual airplane, are you kidding? Everyone loved John, so now it’s time to finally say goodbye to ol’ MKC and start line training at Newark and JFK domiciles. This took 91:30 hours of panel time in L749, L749A and L1049G’s to check out with a two-day, six-leg trip flying paying customers all the way. My time “before the mast” totaled 1,165.5 hours in the three Connie models. During this time, I trained 13 Connie flight engineer students and ended up as check flight engineer in Boston.

Pre-Flighting a Connie

While the two pilots were in the warm confines of the flight planning room drinking coffee, etc., yours truly hauled his big Samsonite suitcase and an even heavier “brain bag” containing several large manuals for each Connie type plus a tool kit. This was schlepped up a skinny 12 foot “engineer ladder” through the small “engineer door” to be deposited in the cockpit. I would start with the cabin interior, before the pax arrived. If it was a very cold day, I would ask one of the flight attendants to sit in the flight engineers’ seat and watch two red lights – if they illuminated, it meant the avgas fueled heaters had caught fire and she was instructed to push the related fire extinguisher buttons and holler for me, as I would be on the ramp under the airplane or up on the wings doing my preflight. Pushing the engineer ladder behind the wing root, I would step up on the wing – if it was slippery with frost or water, I was instructed to hold the big screwdriver in my right hand and if I felt I was losing my footing, punch the screwdriver into the wing. It’s a long way down – a mechanic at La Guardia slipped off a wing one night and broke his neck and died. All maintenance would do is put a patch of “500 mph” Mylar tape on the hole. (It works – I once flew a B707 from London to New York after a lightning strike bored a hole in the wingtip.) Up on the wing, I would “stick” three gas tanks, two oil tanks and on the initial leg, the hydraulic reservoir in the left wing root. Maybe it was just to put the fear into us, but we were told that if we did not secure the door properly, the aircraft would become uncontrollable. Anyway, you were very alert to your surroundings up on those wings. Now, do all this (except the hydraulic reservoir) on the other wing. Then it’s down the ladder and a lengthy pre-flight of the underside of the aircraft, especially in the landing gear bay, exposing all kinds of potential for leaking hydraulic, fuel lines, oil lines, landing gear, outflow valves, etc. Lots to check! Then back up the ladder to the cockpit to relieve the flight attendant and set up the flight engineer panel and study the discrepancies written up in the log book and the mechanic signoffs, so I can brief the captain.

Truth to tell, “you could throw the co-pilot out the window as it took two people to operate a Connie; the captain to fly it and the flight engineer to run all the systems.” The only engine controls available to the captain were four throttles and a single switch to “gang the propellers down” in case of an over-speed. The most awkward posture occurred on takeoff with your right arm extended downward to reach the pressurization switch to “close up” the cabin just after liftoff, while simultaneously reaching up with your left arm to keep a hand on the throttles. “Close up” on the L1049G was somewhat more automatic, so not quite so much of a stretch. Engine starting sequence was 3-4-2-1 with the co-pilot calling out “8 blades” and then “contact 3” whereupon the co-pilot or captain would turn the mag switch to “both” and the reward would be big clouds of smoke and some fire as the big ol’ Wright began to wake up, cylinder by cylinder. The only time the flight engineer got to observe the engines was #3 and #4 and then only if it was a L1049G with the porthole in the crew door. Otherwise, there were no visuals for the engineer, unless he walked back to the cabin area and peered out past a passenger. We sometimes did this, as a PR move to allay the fears of a passenger who told a flight attendant “there’s a lot of oil streaming out of that engine.” “Yep, there sure is!”

Blower Shift

Along with the nighttime pyrotechnics show, once in a while in an attempt to evade ice and/or turbulence, the captain would decide to climb, necessitating the dreaded “blower shift.” What a circus this was! First, the captain makes an announcement to the passengers about this weird thing that is about to happen – he explains that sound levels will decrease, as power on two engines at a time will be reduced to idle, while the flight engineer “shifts blowers” (superchargers) and they will feel a “thump” as the blowers shift for more climb power. The aircraft is usually pretty far up in its “sweet spot” at maybe 14,000 to 16,000 feet when I get the nod from the skipper. Pulling back #1 and #4 throttles, I’m yanking those big blower handles down and praying that they both shift into “high boost.” Now, while I’m doing this, the aircraft is starting a nose high mush trying to maintain altitude. As quick as I can, when I hear the “thump, thump” I bring #1 and #4 back to climb power and bring #2 and #3 throttles to idle and repeat the procedure. All this time poor ol’ Connie is mushing along usually starting to fall out of her altitude and, by the time this thing is completed, even at climb power we are just mushing along, trying to gain climb speed again. Just a day in the life of a Connie crew! The worst day I ever had with the procedure was when I had a flight engineer student on his first line trip – he did not one, but two of them! Being new to the procedure, he was naturally a little slow and to top it off, the reason for the blower shifts were attempts to climb out of icing. Most students didn’t get to do one for real until they were checked out early in their Connie days. Very interesting occupation for sure!

Melt Down

Come spring of 1967 and one of my classmates was the flight engineer on the last revenue flight of the Connie from JFK to St. Louis with a number of stops on the way. There was a “retirement ceremony” for her and my friend received a nice desk model of a Hamilton Standard propeller and other stuff. Soon the Connies were all flown to Mid Continent Airport near Kansas City and home to TWA’s giant maintenance base. There, the once proud flagships were crushed and fed into a huge smelter reducing them to aluminum ingots. The same fate awaited my beloved B707’s fifteen years later. The engines were mated to American Airlines’ airframes to augment the fleet of USAF KC-135 tankers. I normally don’t tell “war stories” but here are three interesting flights in the Connie.

The Purple Spear

We had been in solid clouds near thunderstorms for quite a while when the windshield started to display a “light show” of what looked like miniature lightning strikes dancing all over the glass. The captain explained “that’s St. Elmo’s fire,” which is a heavy concentration of static electricity. New to me! Soon after, the captain said, “Hey Bob step up here and look out the front windshield. Wow – a purple spear was jutting out from the nose and it was growing longer as I watched! Looked like a unicorn’s horn. It continues to extend forward for several minutes – I went back to check on my panel, when BANG! A really loud explosion, the cockpit lit up in blinding light and a FIREBALL shot out of the throttle pedestal racing behind my chair and disappeared under the cockpit door. A wide-eyed flight attendant burst through the doors and said “What was that? A fireball just raced down the aisle and disappeared into the aft bulkhead.” We chuckled and told her what had transpired up in the cockpit. Our vision was slowly returning from that blinding flash, the radios, which had quit working, came back on line and we settled down for what became a routine flight thereafter.

A Close Call

We were descending in moderate icing into the old Downtown Harrisburg Airport – it’s ringed by low hills in kind of a low spot. Props wetted down with the alcohol slingers, boots pumping away when suddenly about five miles from the outer marker, we started taking on an incredible load of ice. Like nothing I have experienced before or since. Did I mention it was a dark and stormy night? At the outer marker, the captain called for “METO power” (maximum except takeoff). We could feel the ol’ girl wallowing – the ice load was increasing so fast – weather was reported at minimums and we all knew there was no go-around tonight. The captain called “More power Bob!” Just past the threshold, the captain slammed the throttles to the firewall, Connie lurched and then gave up any more intention to fly. We fell onto the concrete with a resounding thud and never was I so glad to be earthbound again. After the crew departed for the warmth of the office, I did a walk-around, under the glare of the terminal floodlights. The old girl was one big popsicle – how she held on with that load of ice for that long is amazing to me. Ah well, another day of….

The Great Blackout

On a crystal clear night, flying from Cleveland to New York on November 9, 1965, as we approached the New York area, we got a call from ATC that New York City was blacked out and directed us to a holding pattern over Newark. Turned out Newark was on another power grid and the place was its usual blaze of lights. But, looking out across the Hudson River, New York City, Long Island and everything up the Long Island Sound was lost in the inky black. Eerie business. A Niagara power failure blacked out all the east coast cities to the north of New York City. I have never witnessed so many rotating aircraft beacons as I did in that holding pattern. After a long hold, being laddered down 1,000 feet at a time, we finally landed at Newark.

Some years later, I was flying as first officer on the B707 and I asked the captain “Where were you the night of the blackout?” He replied “I was flying a B727 into JFK with an FAA inspector on the jumpseat. About five miles out I noticed the runway lights getting dimmer but with no comment from the Fed, I just kept coming. The lights were pretty well gone when I touched down wondering if I was going to get a violation but I guess the Fed wanted to get home as much as I did. Taxiing on a totally black surface took a long time but we finally made it to the gate.”

“Uncle Howard”

No article about the Connie would be complete unless it included a comment about her “Uncle Howard” as TWA pilots referred to Mr. Hughes. By the way, the Army really got upset with him when he and Jack Frye delivered a Connie from Burbank to Washington, DC, setting a speed record. Instead of Army war paint, he painted it in TWA livery for promotional purposes. Anyway, the story I want to tell you is this: One day I was conversing with an old-timer flight engineer and he told me this story about his association with “Uncle Howard.” He was Hughes’ personal flight engineer and “He would call me up and tell me to go over and prepare ship number so-and-so for one of his “trips to nowhere” with a bunch of his Hollywood friends. He would call Dispatch and say “Cancel the trip for number so-and-so, I’m using it tonight.” The dispatcher would protest saying “That airplane is all fueled up and provisioned for Paris tonight!” and Hughes would respond “Cancel it, it’s mine tonight.” So it was just him and Howard, no co-pilot. He would take off from New York, head east out over the Atlantic and after setting up for cruise, he would engage the autopilot and say “OK, you got it.” He would then go back with his pals, where the drinking, gambling and “other stuff” were in high gear. The flight engineer would “mind the store” for a few hours; finally Howard would return, turn the aircraft around and head back to New York. “It was his personal toy and he enjoyed it” said the old flight engineer. There are many legendary escapades about “Uncle Howard” but I have enjoyed this one especially.

Another one of “Uncle Howard’s” high jinks – he commandeered an L1649A, loaded it up with his cronies and flew off to wherever. A couple of weeks later it was located on a ramp in Canada. TWA demanded to have it returned but Howard refused – after a lot of wrangling, they finally flew it back on the line.

Bob transitioned to the B707 in 1967 and finished his career on the L1011 but those stories will have to wait for another article. I’d like to thank Bob for sharing his first-hand account of his flight engineer days on the mighty Lockheed Constellation and hope you‘ve enjoyed them as much as I did. Bob gave a presentation on his 2 1/2 years as a Constellation flight engineer at the Yankee Air Museum on November 1, 2017. Here’s a link to a YouTube video of that presentation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uOcUh3jFt0

Connie’s history (Ralph M. Pettersen’s version of the Golden Age of Flight)

1940 – 84 civilian orders – 40 each from TWA and Pan American for model 49. USAAF ordered 313 C-69s – 2,200 HP Wright Double Cyclone engines. Only 15 C-69’s delivered by war’s end, so this allowed civilian airlines to revert those remaining Connies to be painted in their livery by November 1945.

1945/1946 – Pan American to Bermuda. TWA New York to Paris now took nearly 20 hours with refueling stops at Gander, Newfoundland and Shannon, Ireland. TWA soon added Cairo, Lisbon, Madrid and New York to Los Angeles. 1947 – L749 with 2,500 HP Wrights and additional fuel capacity allowing maximum takeoff weight increase from 86,250 pounds to 102,000 pounds. She beat other airline’s unpressurized DC-4’s by 2-3 hours between New York and Los Angeles (11 hours for the Connie). However, the DC-6 was a real contender. The L749A was TWA’s longest serving Constellation model with 19+years of service between March 1948 and May 1967. All models were carbureted to this time.

1951 – L1049 Super Connie with Wright R3350, 2,700 HP engines and stretched 18 feet 4 inches. Gross weight increased to 120,000 pounds with rectangular windows replacing the circular ones.

1953 – L1049C now with “turbo-compound” 3,250 HP R3350 engines with three “blow down” power recovery turbines (PRT). We called them “parts recovery tubs.” These PRTs converted exhaust gasses into another 550 HP. Fuel consumption was reduced by 20% due to fuel injection. Flight test began in February, four months ahead of the DC-7. Weight now 133,000 lbs. At this time, the joke around the pilot’s flight planning room was “the world’s best tri-motors” thanks to those new turbo compound engines. Two important stops once a month were Cairo and Bombay. Toothbrushes were used by a small army of workers to clean the interior and polish the bare aluminum skin to a gleaming finish.

1955 – Best Model – L1049G (Super G) – 3,400 HP, 600 gallon tip tanks (7,750 gallons total). This was the first airliner to make a schedule based on a 350 mph cruise speed. Some grossed out at 140,000 pounds. Another special piece of equipment on the L1049Gs was the engine analyzer, or as the flight engineers called it, “The Chinese TV.” The flight engineer could see every spark plug and electric unit on the engines, which was a big part of the engine run-up before takeoff (some captains got antsy waiting for the flight engineer to complete this procedure). We had fistfuls of cue cards for all the possible maladies. One day I saw a “double shorted secondary” meaning busted cylinder/shutdown.

1957 – L1649A Starliner carried 9,600 gallons of fuel with a max takeoff weight of 156,000 pounds. Initial deliveries were made in 1957, a year after the DC-7C and just 16 months before the B707. Turbo props might have saved her for a while. TWA flew the polar route from London to San Francisco and Los Angeles. The crew complement was 4 pilots, 2 flight engineers and 2 navigators. Los Angeles to London was scheduled 19 hours and 10 minutes. Return to San Francisco was 21 hours and 5 minutes. Only 44 L1649A’s were built and they were the last piston engine airliners produced by Lockheed.

A total of 856 military and civilian Connies and Super Connies had been produced when production ended in 1958. During Connie’s lifetime of approximately 27 years of scheduled operation, she set 45 major commercial airline speed records. TWA operated 146 Connies at one time, more than any other airline.

After Howard Hughes & TWA President Jack Frye flew Constellation #2 from Burbank, CA to Washington D.C in the record time of 6 hours 58 minutes nonstop, the Constellation was flown up to Dayton, Ohio at Wright Field where Orville Wright boarded the new super-plane 41 years after his historic flight of the Wright Flyer at Kitty Hawk , North Carolina. Wright sat at the controls of the Connie for a few minutes. This flight on April 26, 1944 would be Orville’s last airplane flight. This was the only commercial airliner to be flown by the pioneer of flight. (Hughes had the military C-69 painted in TWA livery against regulations for the publicity from setting the commercial speed record.

May 1986 – L1049H Super Connie N6937C had been rotting away in a Mesa, Arizona boneyard for a number of years. An organization called “Save-A-Connie and consisting of volunteer veteran TWA mechanics spent 3,000 man hours preparing it for a ferry flight to Downtown Kansas City Airport. Three years of restoration including replacing 700 pounds of old tube type gear with 70 pounds of digital avionics. Four main tires worth $900 apiece were donated by BF Goodrich. New batteries were $500 each. For a number of years the Super Connie flew the U.S. airshow circuit but she has been grounded since 2005 and is currently on static display in Kansas City. She burned 400 gallons per hour in cruise with the engines detuned for 100LL. Oil 2.5 gallons per hour per engine. 41 gallon oil tank kept at a minimum of 31 gallons.

Ralph M. Pettersen, December 2017

Photo Credits: Bob Garrard, J. Roger Bentley, Jon Proctor, R.A. Scholefield, Ralph M. Pettersen

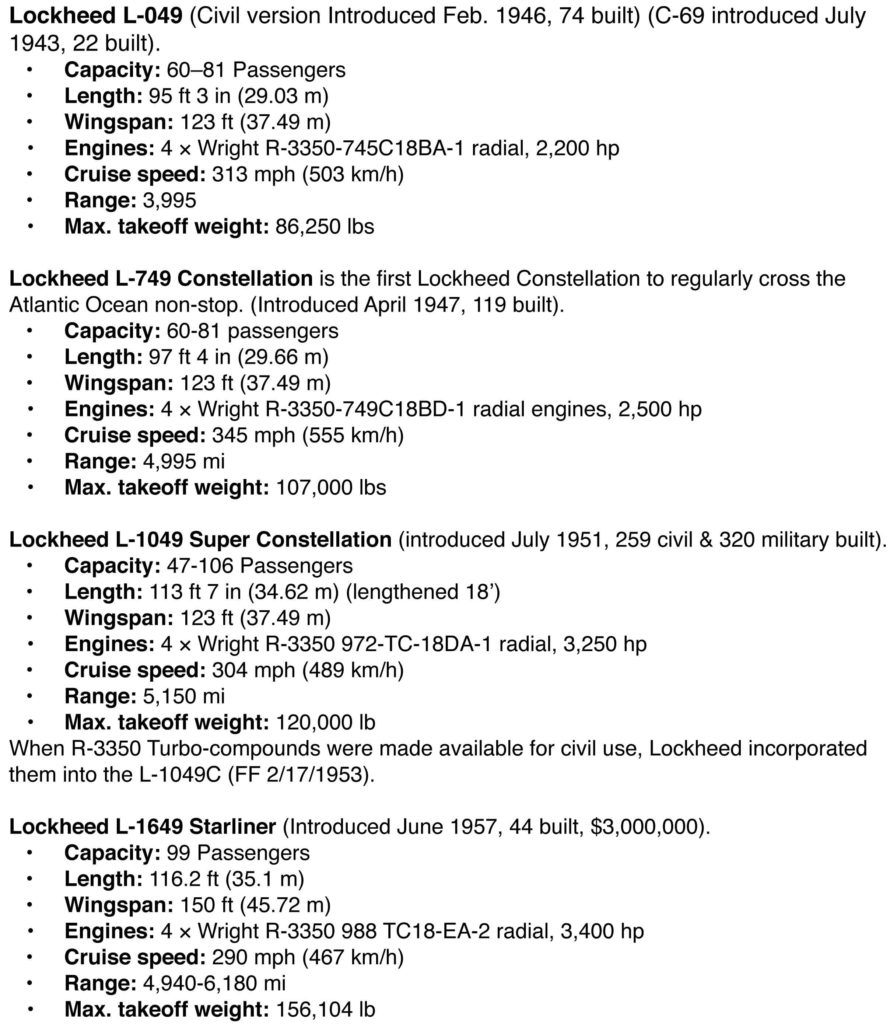

Constellation Model Specifications:

Flying Constellation Survivors:

The Historical Aircraft Restoration Society Connie is one of only two flying L-1049 Super Constellations in the world. The other is the Breitling Super Constellation in Switzerland. Amazingly both aircraft were built next to each other in the factory. HARS’ Connie is #4176 and Breitling Constellation is #4177. An L-1649A Super Star (the last model of the Constellation line) is currently in the USA being restored to flight by the Lufthansa Museum.

In March 2016, an L-749 Constellation was flown from Arizona to Virginia to be fully restored by Dynamic Aviation. This VC-121A-LO was the original Air Force One used by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. She was known as Columbine II, the very first aircraft ever to have the call-sign “Air Force One” when a president was aboard. (Massey was honored to have Ken Stoltzfus pay us a visit this year. Dynamic Aviation originally was K&K Aircraft, founded by Karl and Ken Stoltzfus in 1967, the company continues the aviation legacy started in 1934 by their father, Chris Stoltzfus.)

For much more information visit Warbirds News:

Columbine II Arrives at Her New Home!!! (March 2016) http://warbirdsnews.com/warbirds-news/columbine-ii-arrives-home.html

Columbine II – 2nd Mid-April 2015 Update http://warbirdsnews.com/warbirds-news/columbine-ii-2nd-mid-april-update.html

Blue Skies prevailed for another great December Fly-In!

After dawning rainy & foggy the weather cleared as predicted for the first plane to arrive at 10:20 AM. With the forecast for sunny & mild (mid 50’s) we were thankfully ready for the expected onslaught that ultimately arrived only slightly delayed. As usual, the grass was firm & dry for the nearly 160 guest planes that arrived by 1 PM. Who knows how many pilots were discouraged by the early weather and chose not to come? There were well over 125 drive-ins and the local car club had a good showing despite the wet roads. December weather has proven surprisingly reliable for us.

We want to express our sincere thanks to the many volunteers that made this a success – both in the kitchen and on the field! And a big thank you to all our friends who brought food items to share.

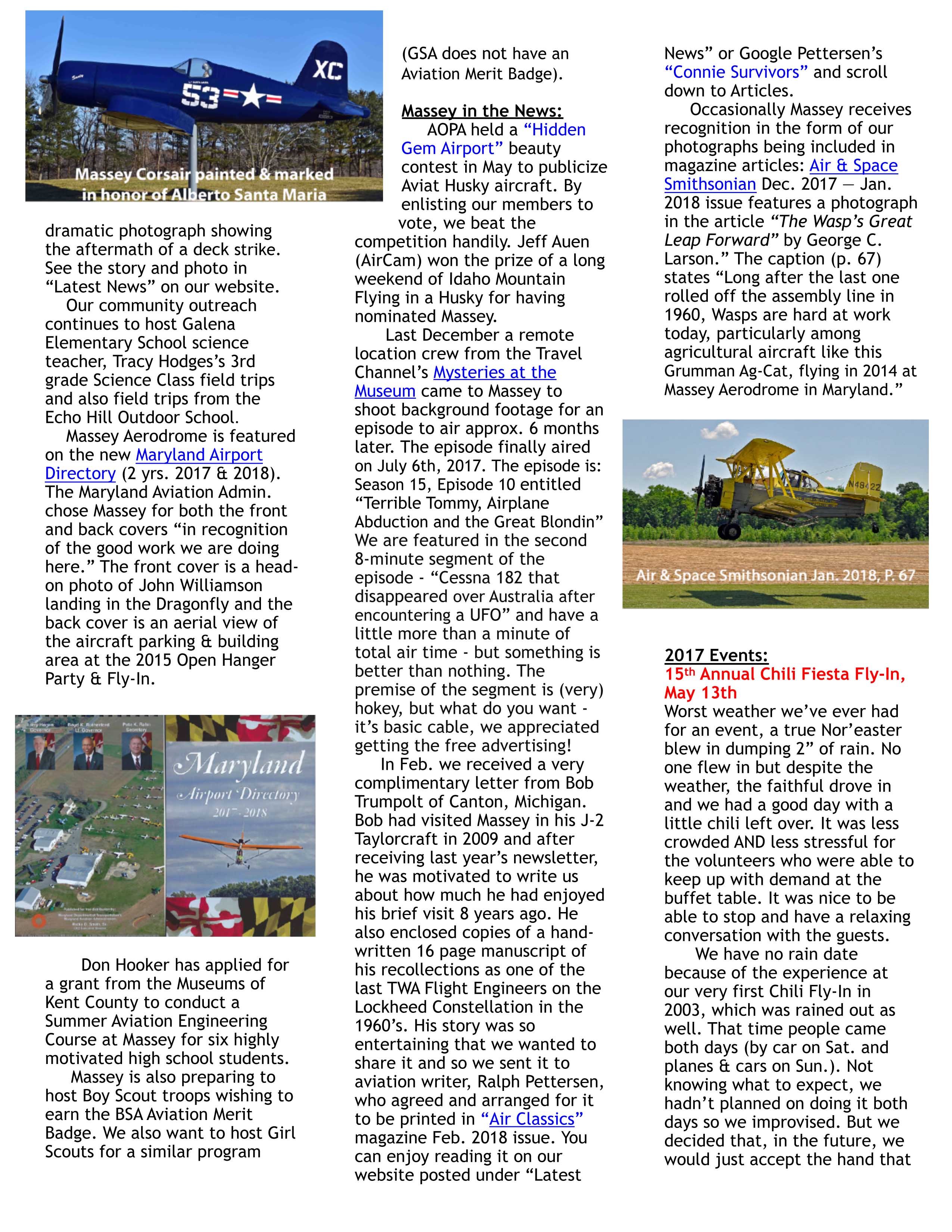

Grassroots aviation means taildraggers with a special place in our hearts for radial engined planes. Four Stearman flew in plus our two in the hangar made 6 on-field. Radial engines included a 1943 Howard DGA-15P, a 1952 Cessna 195 and our favorite BIRD by which we mean Mike Pangia’s “Lindbergh Bird” the 1930 Brunner Winkle Bird N727Y with Kinner power.

Liaison aircraft had a very good showing with six:

Dan O’Donnell’s sparkling Aeronca 7AC newly restored as an L-16 N878

Paul Smith’s very authentic, award winning 1944 Piper L-4H N79731 (#82)

Richard Wallin’s beautiful award winning Aeronca 7BCM L-16 N9325H

Austin Shartle’s newly restored 1946 Piper L-4A “Grasshopper” N87910 (#39) (Michigan?)

Larry Kelley’s unmistakable camouflaged (Giraffe spots) 1958 Aeronca 7FC L-16 N7513E

Jon McLanahan’s 1955 Fuji LM-1 N8020K (Lynchburg, VA). The Fuji is a Japanese license-built 4 place Beechcraft derived from the T-34.

Our friend, John Chirtea showed off his pristine newly acquired 1965 Alon A2 (Ercoupe follow-on) to replace the one he very graciously donated to the Massey Air Museum.

There were 3 gyro-copters (Autogyro GMBH) and one Robinson R44 helicopter, many Piper Cubs & RVs plus uncounted Cessnas and low-wing Pipers.

With one Cirrus and quite a few new design Light Sport planes there was something for everybody.

We repaired and painted our life-size “Corsair” model in tribute to a past friend of Massey, Navy Commander Alberto Santa Maria who flew Corsairs off the carrier USS Palau and became a senior Test Pilot for Boeing-Vertol on the CH-47 Chinook. See accompanying article in “Latest News” below.

Finally, if you are a local resident, please support our sponsors: Atlantic Tractor, your one-stop shop for all John Deere equipment

Finally, if you are a local resident, please support our sponsors: Atlantic Tractor, your one-stop shop for all John Deere equipment

and Twinny’s Place Restaurant in Galena.

More Pictures:

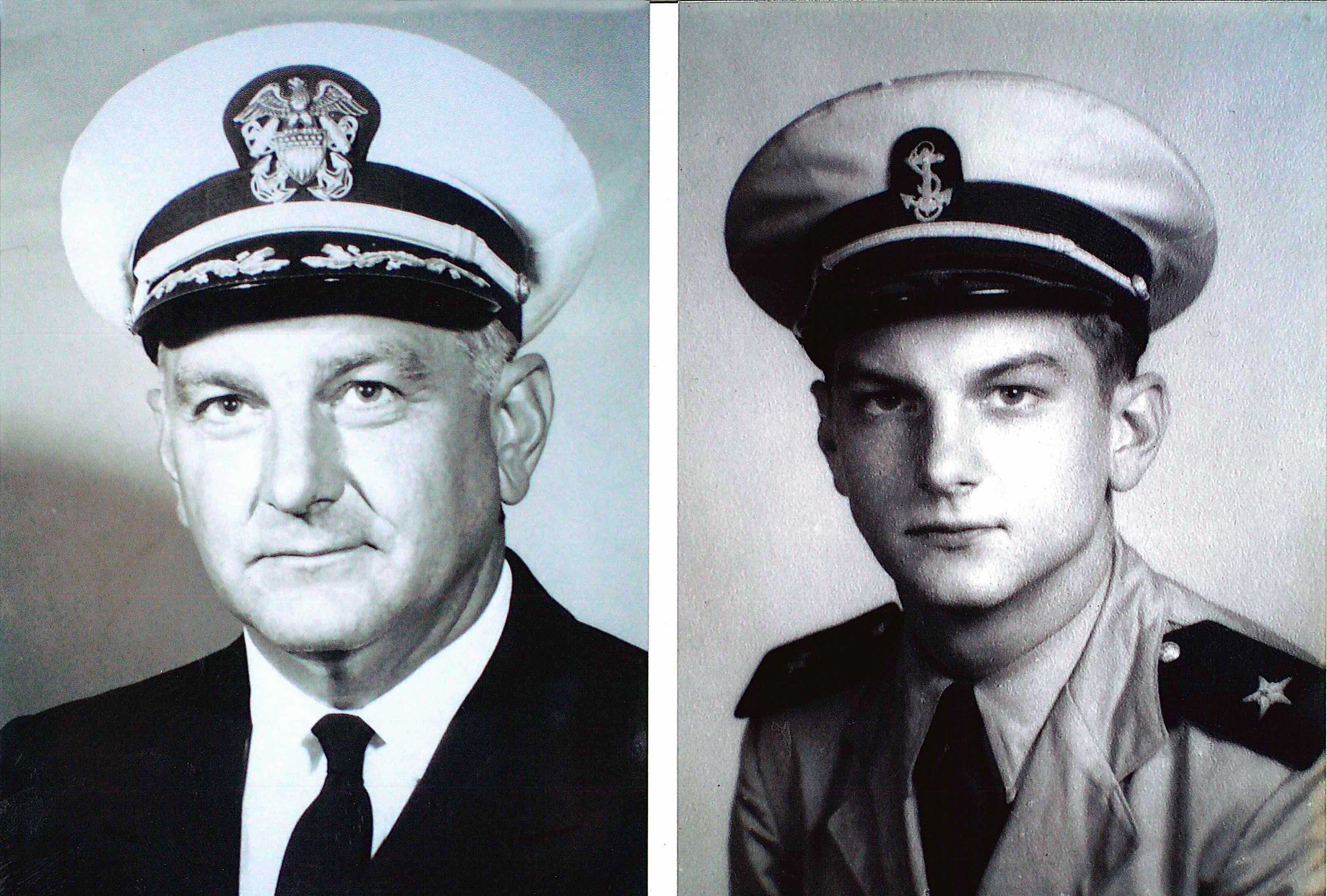

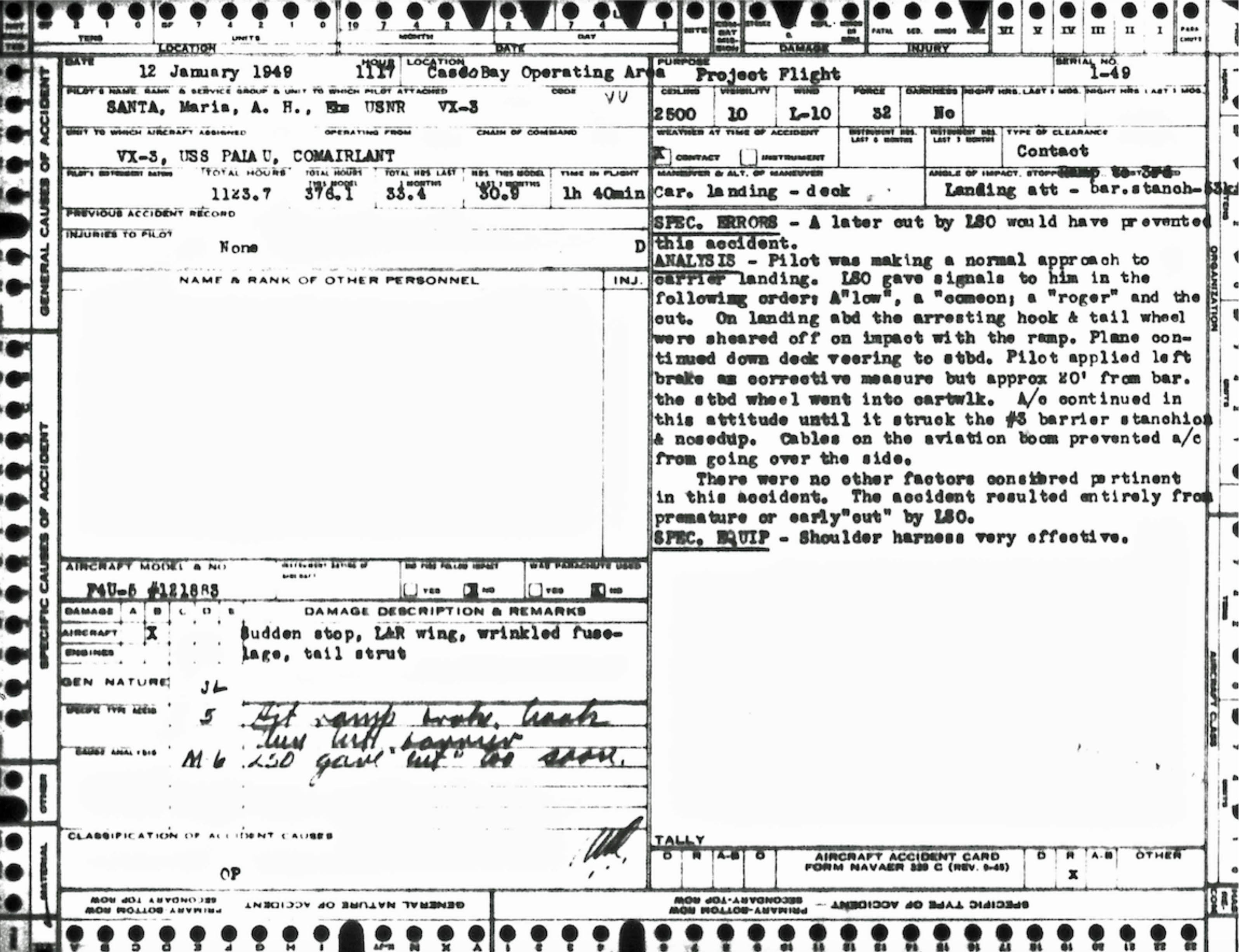

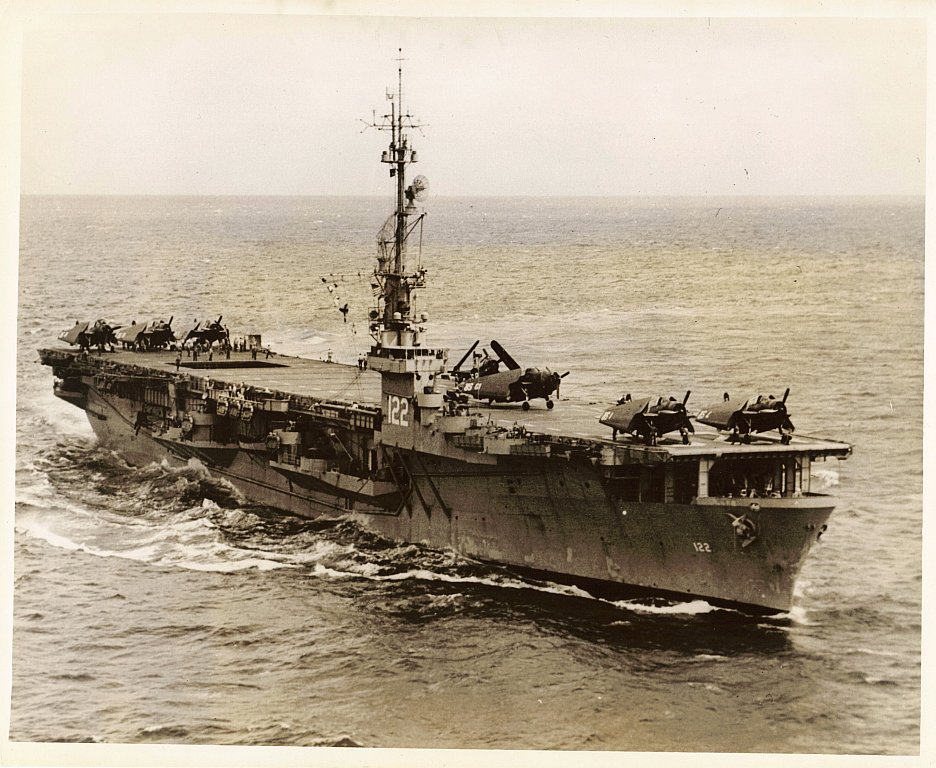

The MASSEY AIR MUSEUM honored Alberto H. Santa Maria, Cmdr., U. S. Navy (1924 – 2010) at the 17th Annual Open Hangar Party & Fly-In held on December 3, 2017. As a tribute to Alberto, our “Corsair” was restored and repainted to represent the F4U-5 Corsair shown in a photo as flown by (then) Lt. Santa Maria. The photo was taken by a Navy photographer after a deck strike accident aboard the USS Palau (CVE-122) in 1949. While on a cruise off Newfoundland with Helicopter Development Squadron Three (VX-3) out of Atlantic City, NJ, Lt. Santa Maria received an early cut command from the Landing Signal Officer (LSO) with the result seen here – however, the LSO, not Santa Maria was held responsible. While this could have been a fatal accident, it was not due to poor airmanship on his part. It is a dramatic photo and Alberto liked to share it, we were privileged to hear him recount this story and many others when he attended previous Open Hangar Parties at Massey Aerodrome where he was a member of the Massey Air Museum.

Alberto went on to have a distinguished career as a helicopter test pilot. Among the achievements of Alberto H. Santa Maria:

Commander U. S. Navy Reserves (RET)

Naval Aviator (F6F “Hellcat”, F4U-4 & 5 “Corsair” & helicopters)

Test Pilot (Navy Exper. & Devel. Sqn. VX-3, tailcode XC)

Senior Test Pilot (Boeing-Vertol) – CH-47 “Chinook”

Engineering Test Pilot (All American Engineering)

Engineering Test Pilot (Atlantic Aviation)

Bell HU-1 A / UH-1 Iroquois “Huey”

Member Society Experimental Test Pilots

Member Quiet Birdmen (“QB”) (Wilmington Hanger)

First pilot to log 1000 experimental hours in the “Chinook”

Performed the first water landing tests in a “Chinook”.

Interest in aviation ran in the family as Mr. Santa Maria’s father (also Alberto) joined the RCAF in 1917 and flew a Sopwith Camel in WWI “over German trench lines.”

Below are Al Santa Maria’s own notes on back of photo of F4 Corsair on it’s nose:

“A Landing Gone Awry” on Jeep carrier CVE-122 Palau shortly after WWII. The straight landing deck is only 400 feet long. The Landing Signal Officer (LSO) called for a throttle “cut” a little too early. The other photo shows the damage to the approach end of the deck. Photo taken January 12, 1949, by a Navy Photographer off the coast of Newfoundland. The ship was working with the Navy Experimental and Development Squadron VX-3 out of Atlantic City, NJ. (Squadron VX-3 had tailcode XC assigned to them)”

Al liked to say “Any landing you can walk away from is a good landing” — He was EXTREMELY fortunate, judging from the damage to the approach deck, a few inches lower would have totally destroyed the plane.

An early model Sikorsky R-5 (Navy HO3S-1) helicopter is visible behind the Corsair’s tail.

Our Corsair is a life-size fiberglass model of an actual F4U-1D Corsair (from which the mold was taken) which was owned by David Tallichet’s Military Aircraft Restoration Company . The model was made by a company also owned by David Tallichet specifically for his Specialty Restaurants business to be displayed outside his World War II themed restaurants. They were able to capture all the surface detail when they made molds from the real airplane – you can count every rivet & dzus fastener. This model was displayed for many years outside the 94th Aero Squadron Restaurant in College Park, MD until obtained by Massey. We dismantled and moved it to the airport in December 2007 and installed it on a new pylon at the airport on June 27, 2009. The paint, having suffered from being exposed to the weather for ten years at Massey and an unknown period at the restaurant, we decided to take advantage of the need to repaint it to change the identity to that of a Corsair flown by a friend of Massey, Alberto Santa H. Maria.

[See also Massey Web Site > Airport News > Corsair Replica Erected: (Link) https://masseyaero.org/projects/corsair/ ]

The Massey Air Museum wishes to thank Chris & Dee Jennings and The Museums of Kent County (MD) for funding the painting and marking of our Corsair in honor of Alberto H. Santa Maria. Thanks also to Bill Lee of the Air Mobility Command Museum (Dover, DE) for repairs and bird-proofing, Nick Mirales for painting and decal application and Chris Jennings for painting preparation.

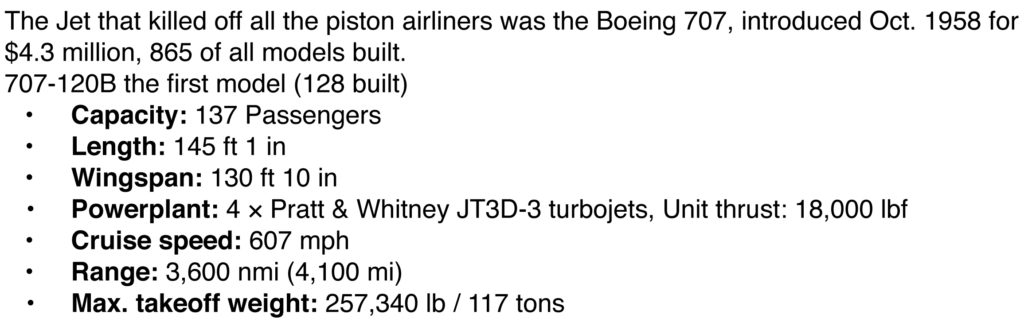

Two Portraits of Alberto H. Santa Maria, Jr. USNR No. C-23305:

U.S. Navy Accident Report January 12, 1949:

BELOW is enlargement of right half of report above:

Stock photo of a different Corsair landing on a carrier, Landing Signal Officer (yellow shirt – left) giving “CUT” signal with the paddles.

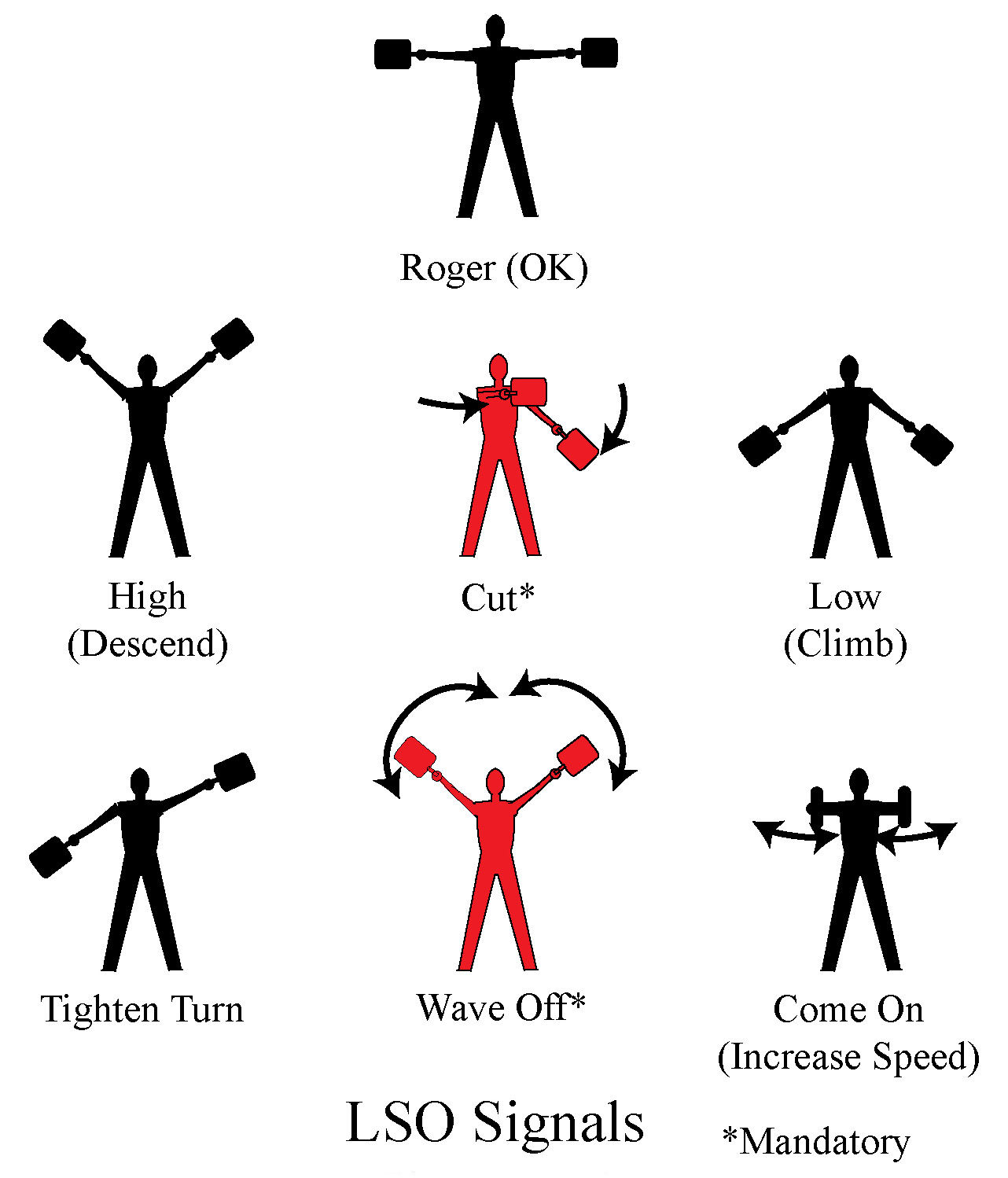

7 LSO Standard Signals (Note two signals are Mandatory):

Alberto H. Santa Maria in McDonnell F2H Banshee:

Transferred from VF-933 to HU-931 NAS Willow Grove, CDR. HS 931. Alberto H. Santa Maria with NAS Willow Grove HS-932:

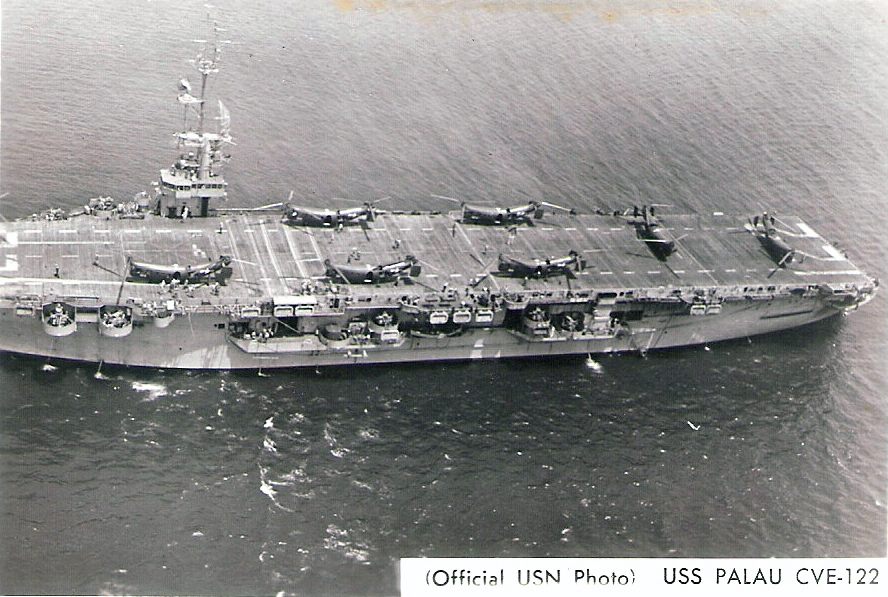

Escort Carrier USS Palau (CVE-122) underway:

Marine Corps Piasecki HRP-1’s (such as flown by Alberto Santa Maria) are shown aboard the USS Palau: