Massey Air Museum, 33541 Maryland Line Road, Massey, MD, 21650

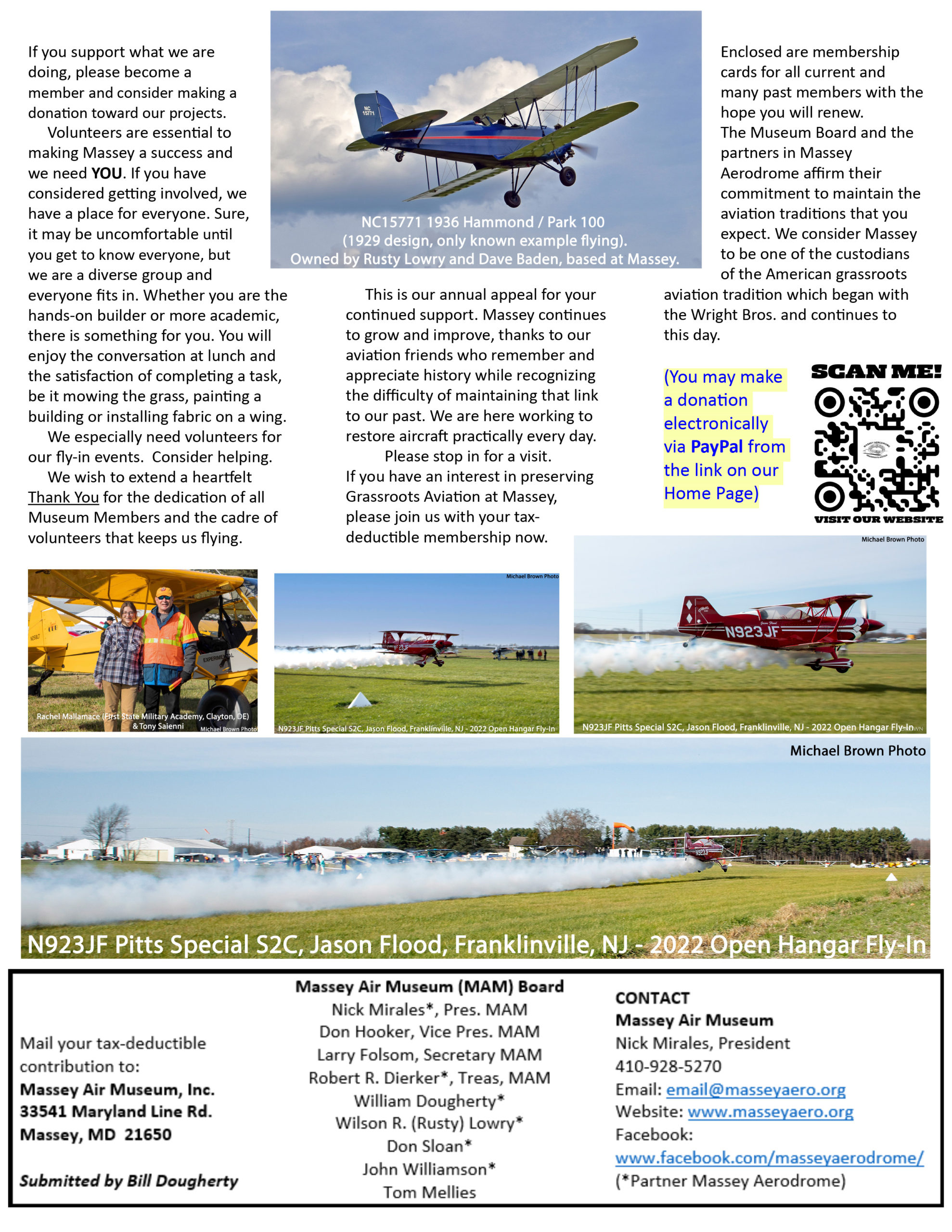

Grassroots Aviation

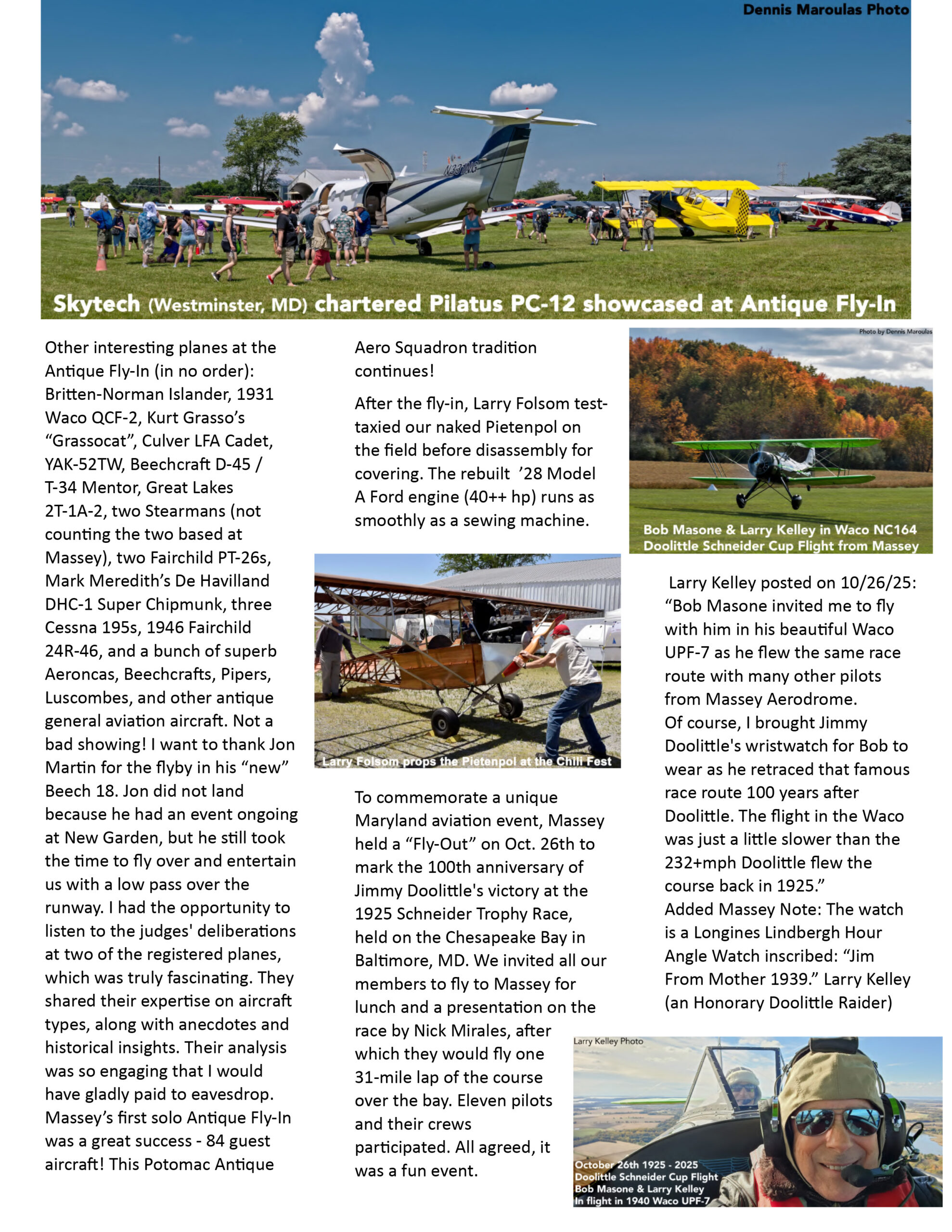

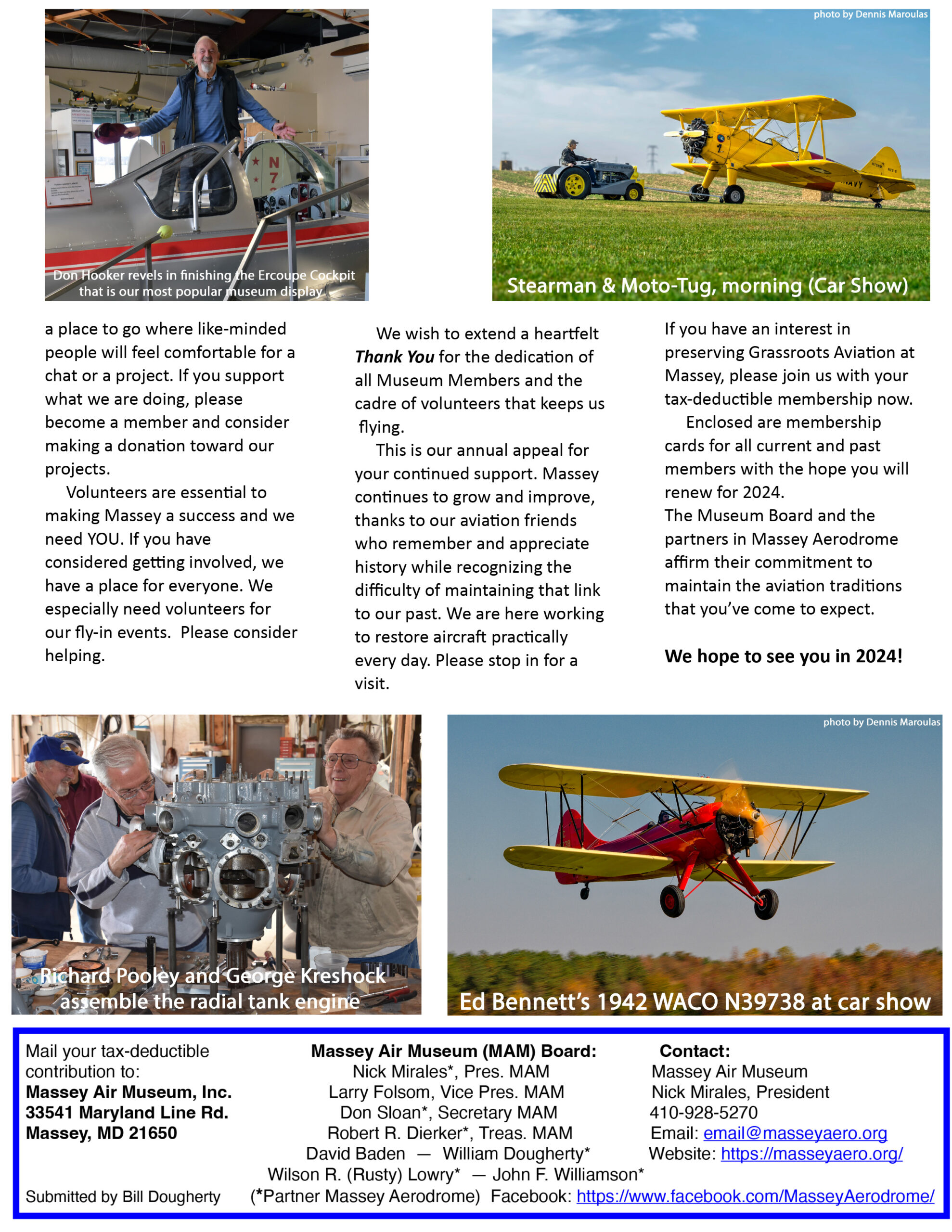

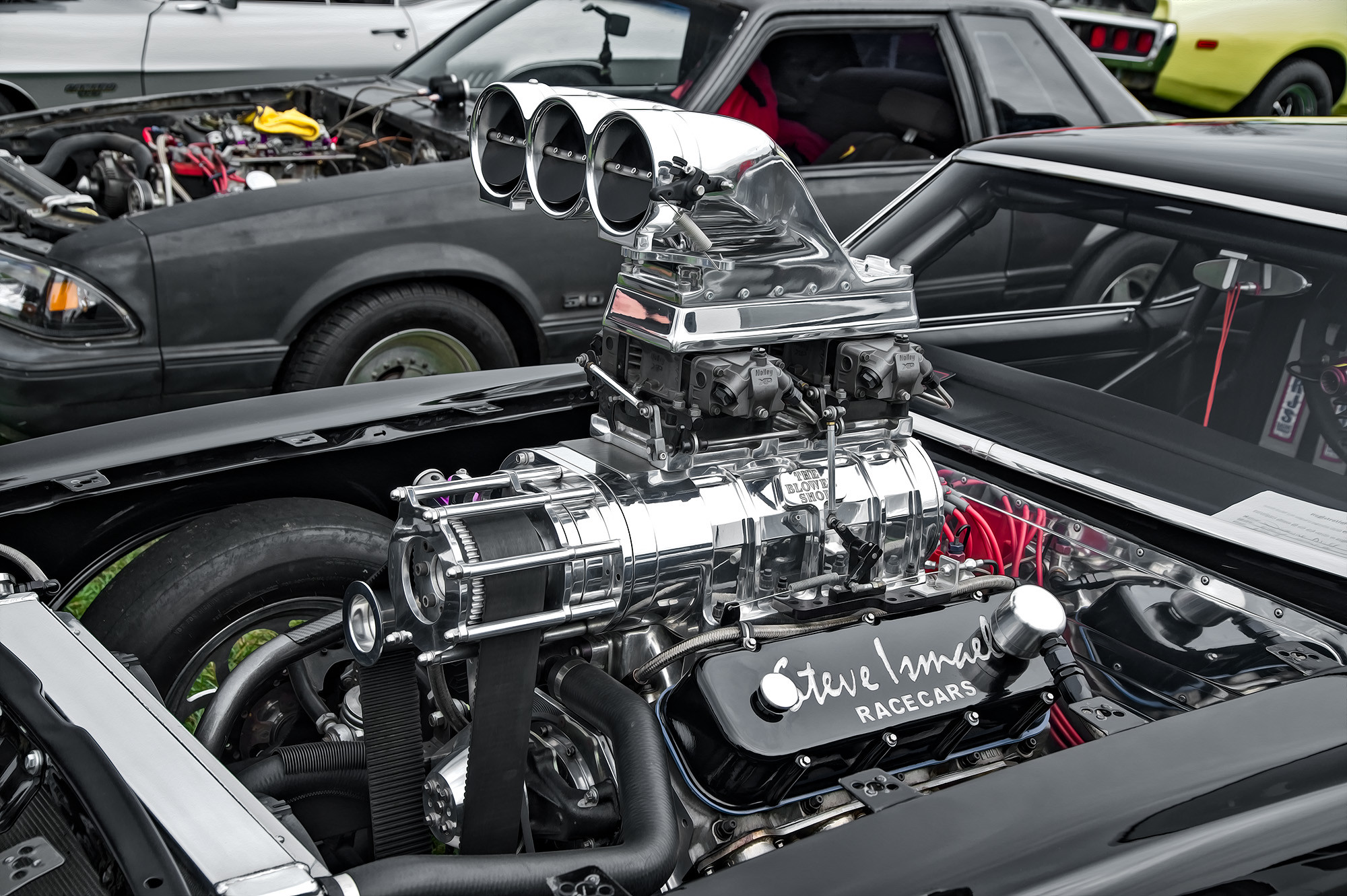

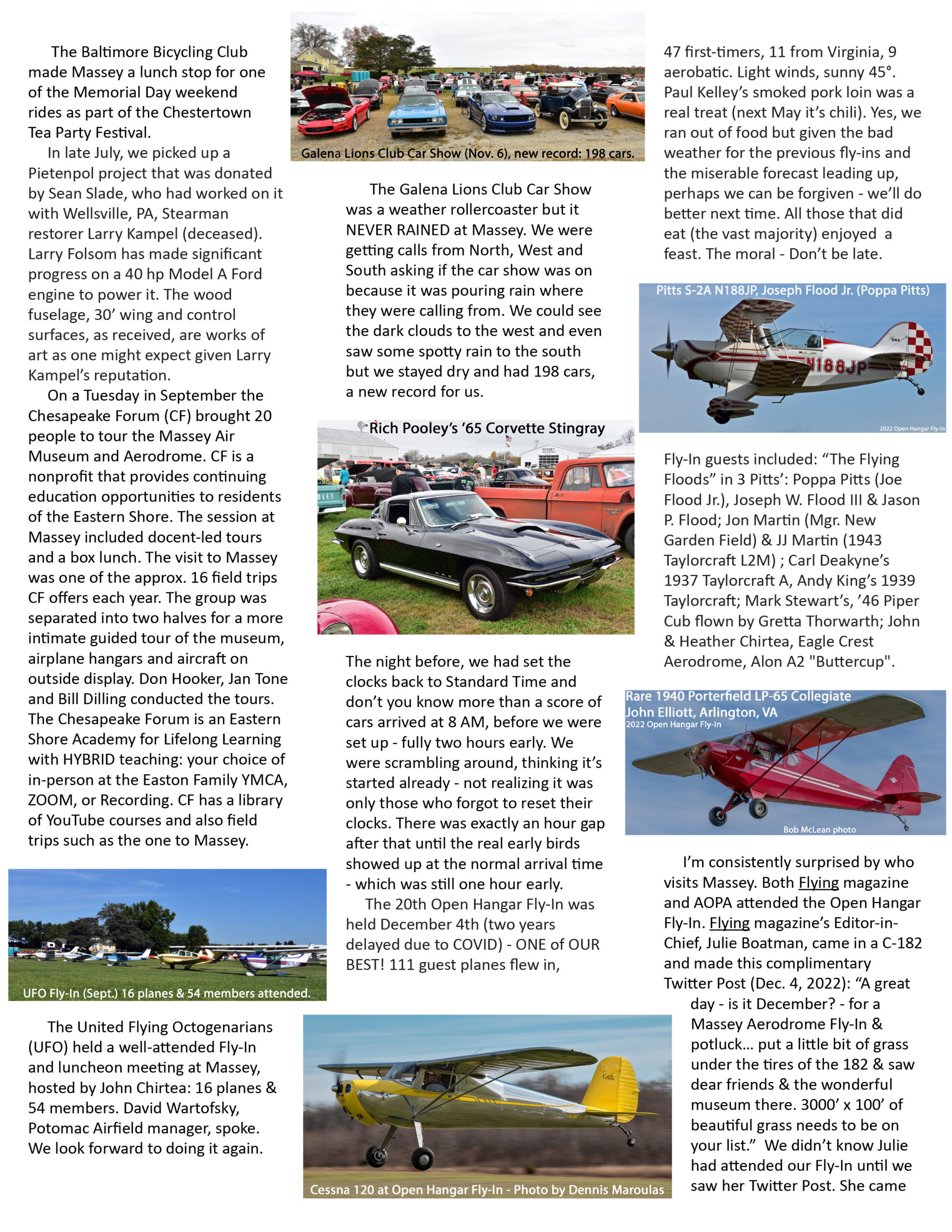

GALENA LIONS CLUB CAR SHOW (First Sunday of November) NOVEMBER 5th: 10 AM – 2 PM {Rain Date Sunday Nov. 12} (This is not a “fly-in” but flying guests & general public are invited to attend – Free Admission.) Car  Registration: 10 AM to 12 Noon with Judging from 12 to 1:30 PM. Awards: 2 PM. Entry Fee for Show Cars: $20.00 (No Admission charge for General Public). The Galena Lions Club annual Judged Car Show is at Massey Aerodrome (no longer at Turner’s Field). Refreshments sold to benefit The Galena Lions Club. We’re looking forward to upwards of 200 show cars on view. Massey Aerodrome is family friendly and handicap accessible (on grass). THE AIRPORT WILL REMAIN OPEN AS USUAL FOR OUR FLYING VISITORS.

Registration: 10 AM to 12 Noon with Judging from 12 to 1:30 PM. Awards: 2 PM. Entry Fee for Show Cars: $20.00 (No Admission charge for General Public). The Galena Lions Club annual Judged Car Show is at Massey Aerodrome (no longer at Turner’s Field). Refreshments sold to benefit The Galena Lions Club. We’re looking forward to upwards of 200 show cars on view. Massey Aerodrome is family friendly and handicap accessible (on grass). THE AIRPORT WILL REMAIN OPEN AS USUAL FOR OUR FLYING VISITORS.

———————————————————————————————

AWARDS: Presidents Trophy & Top Ten Plaque Awards, Dash Plaques to first 50 Vehicles. Door Prizes, 50/50, Chinese Auction, D.J. Music, Food & Beverages.

This event benefits the Galena Lions Club Charities & Massey Air Museum. Additional Info: Call 410-708-4889 or 410-678-5251

P.1

P.1

P.2

P.2

P.3

P.3

P.4

P.4

P.5

P.5

P.6

P.6

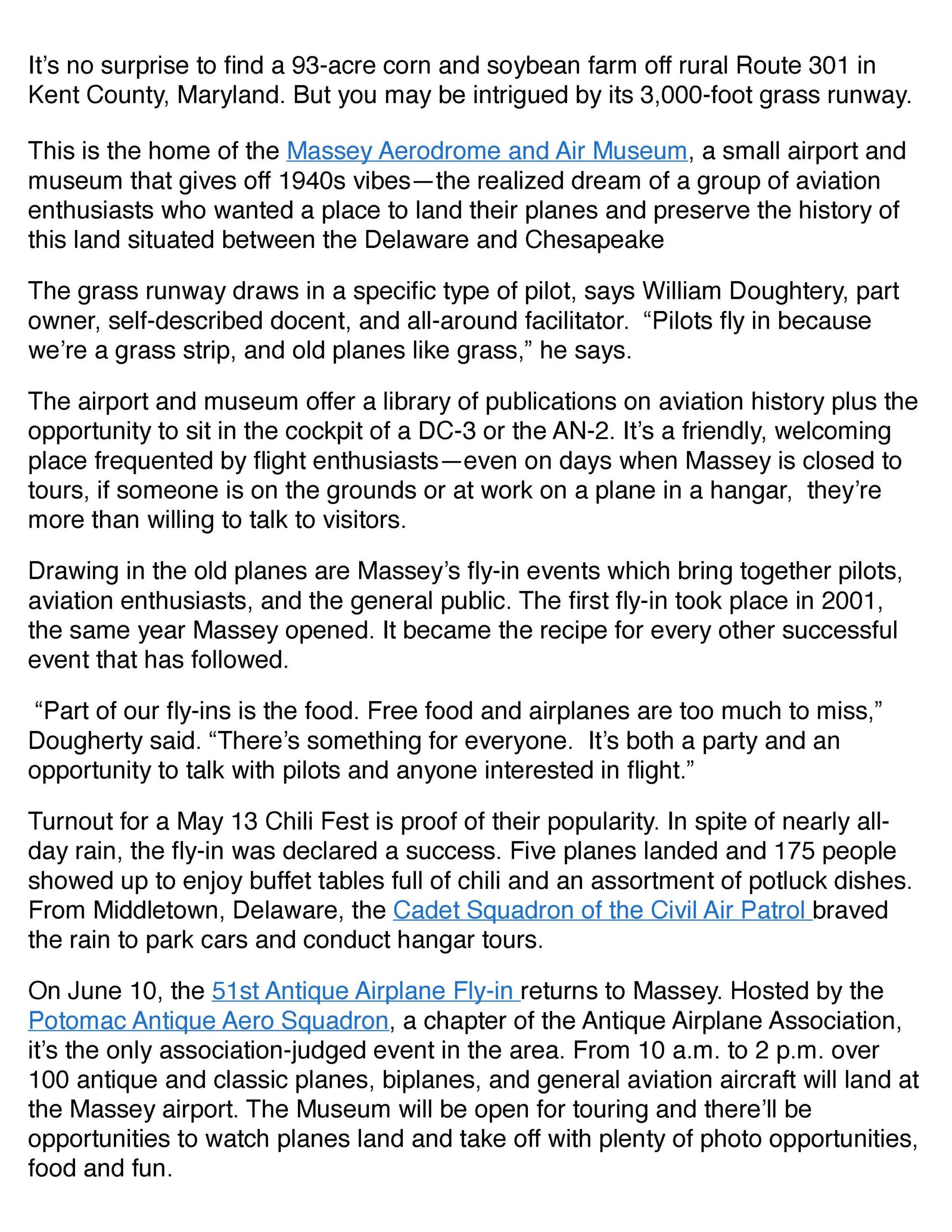

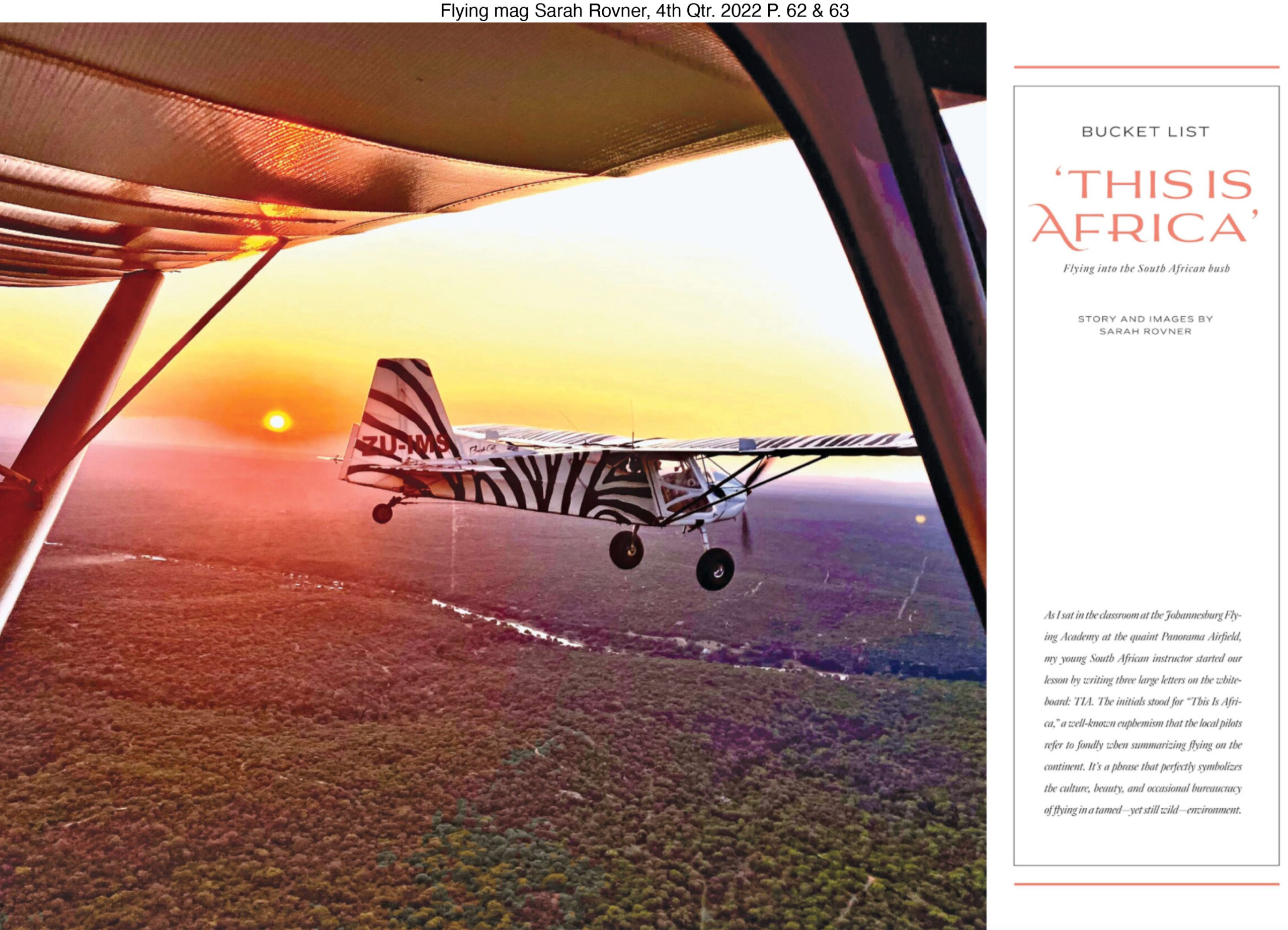

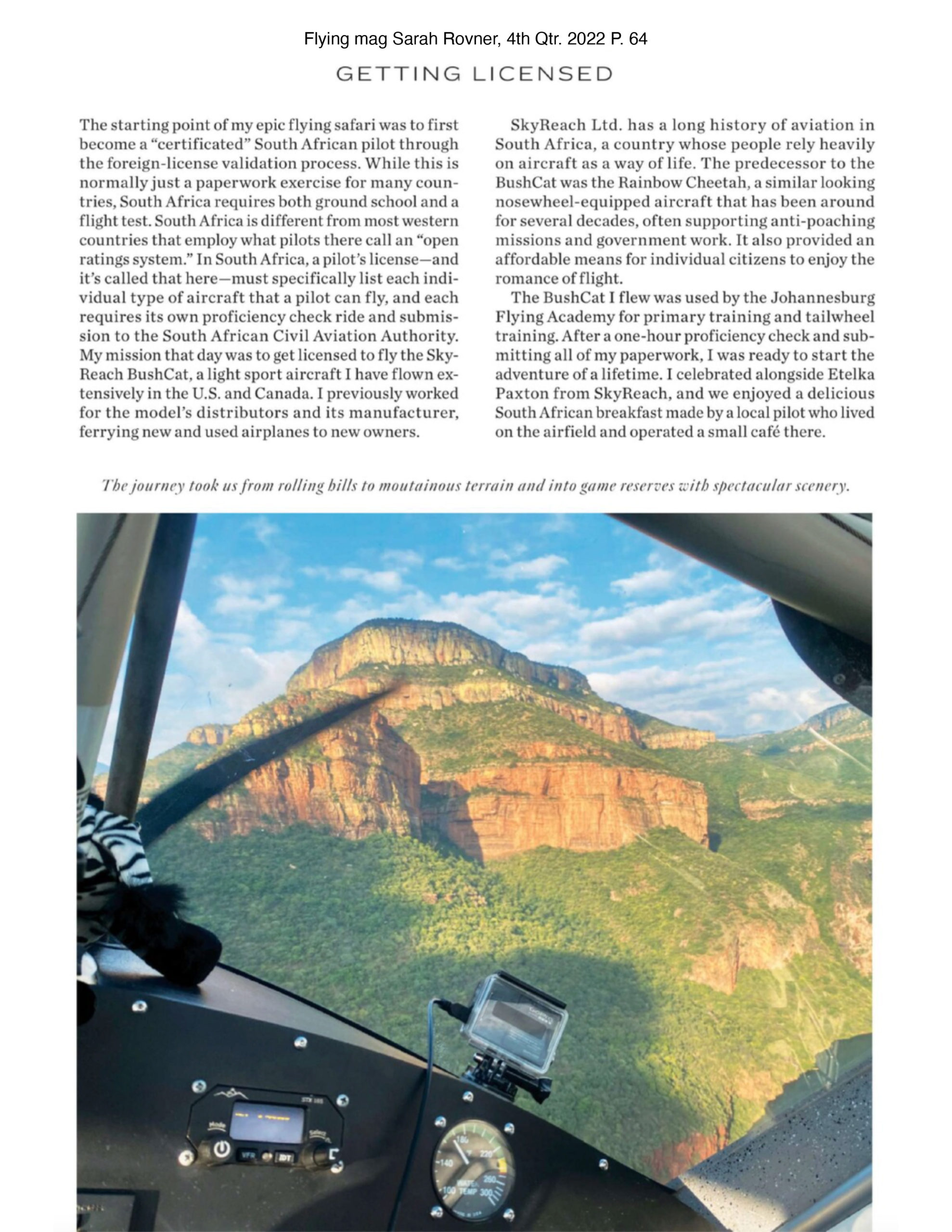

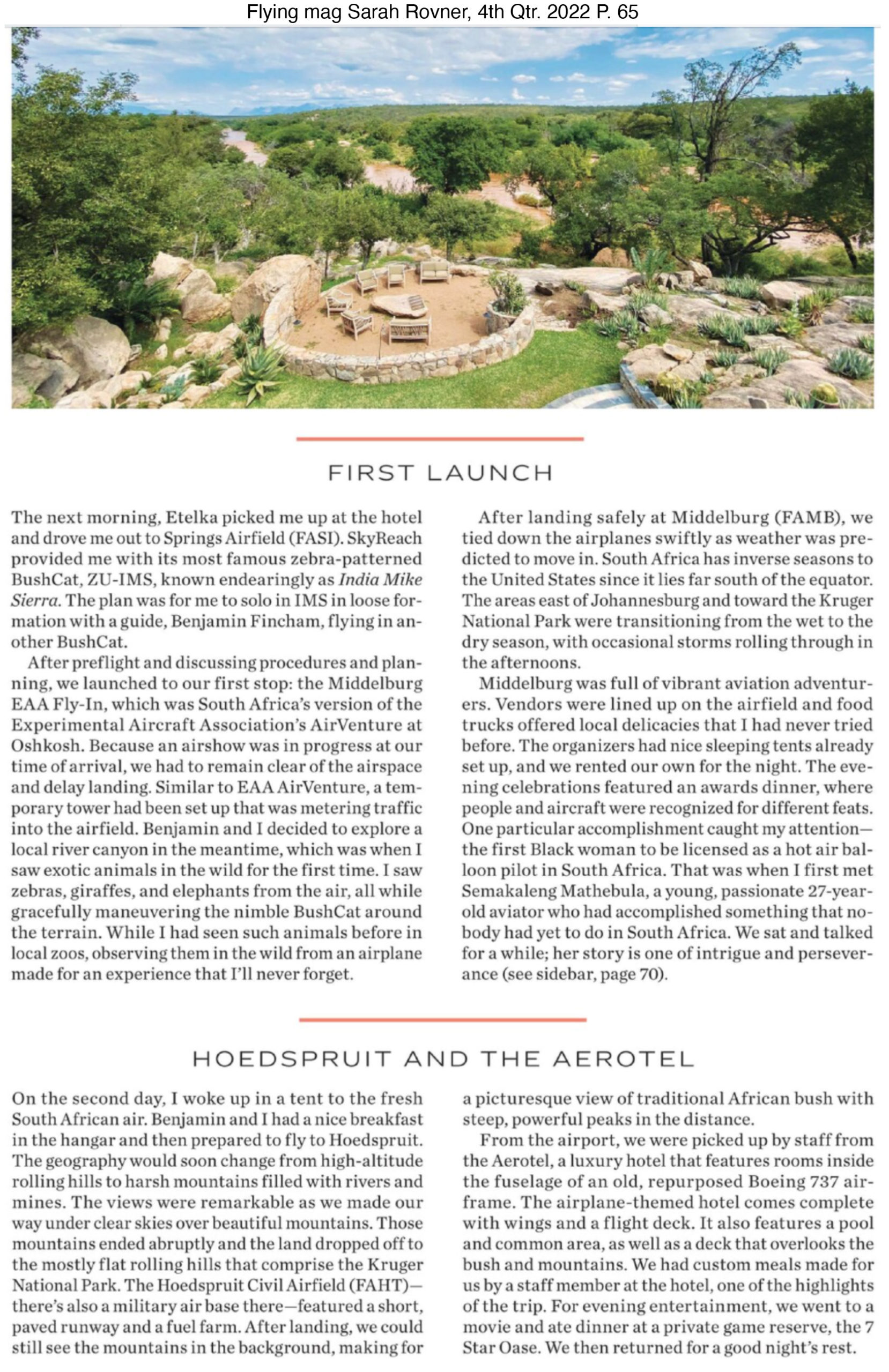

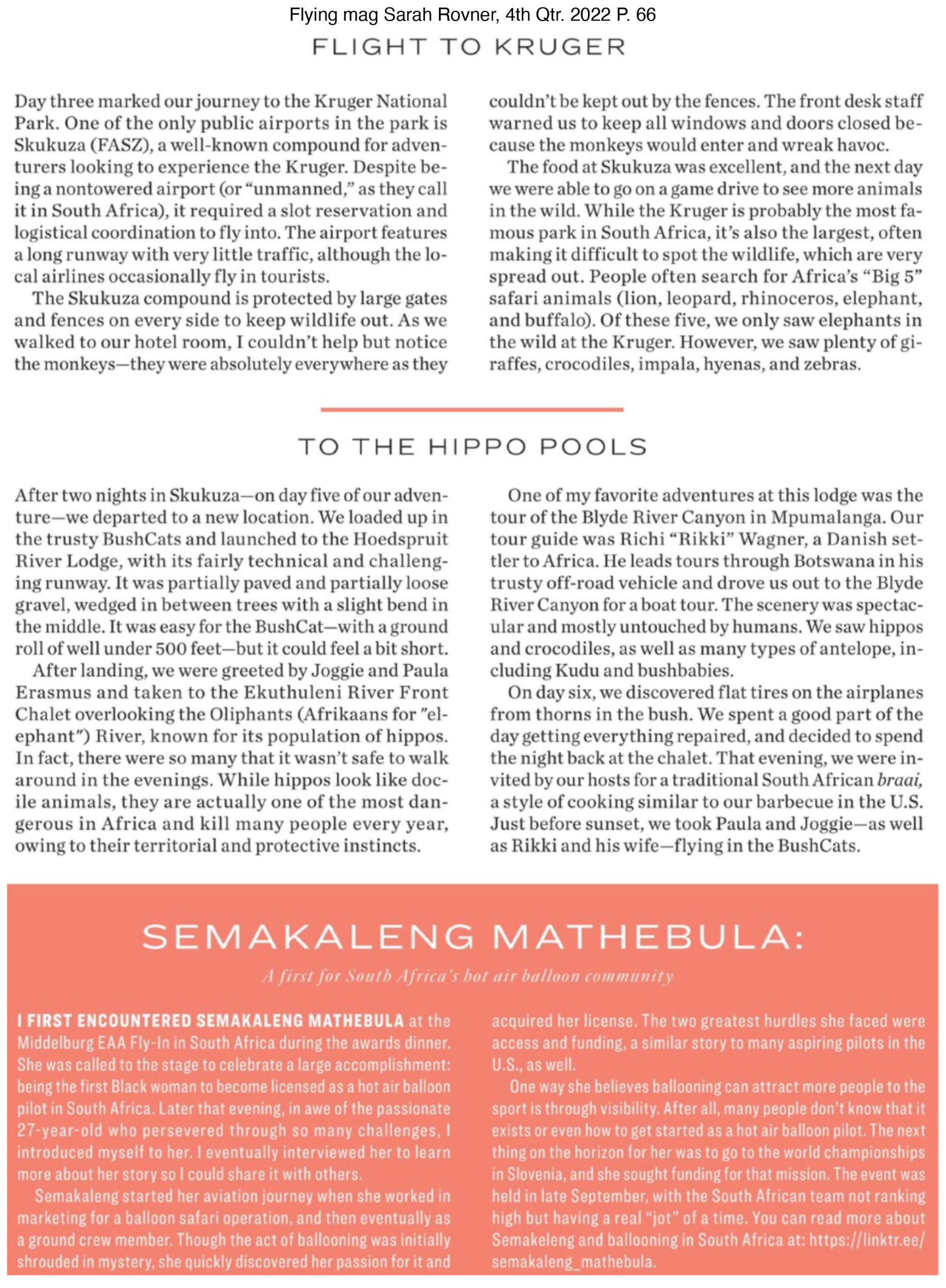

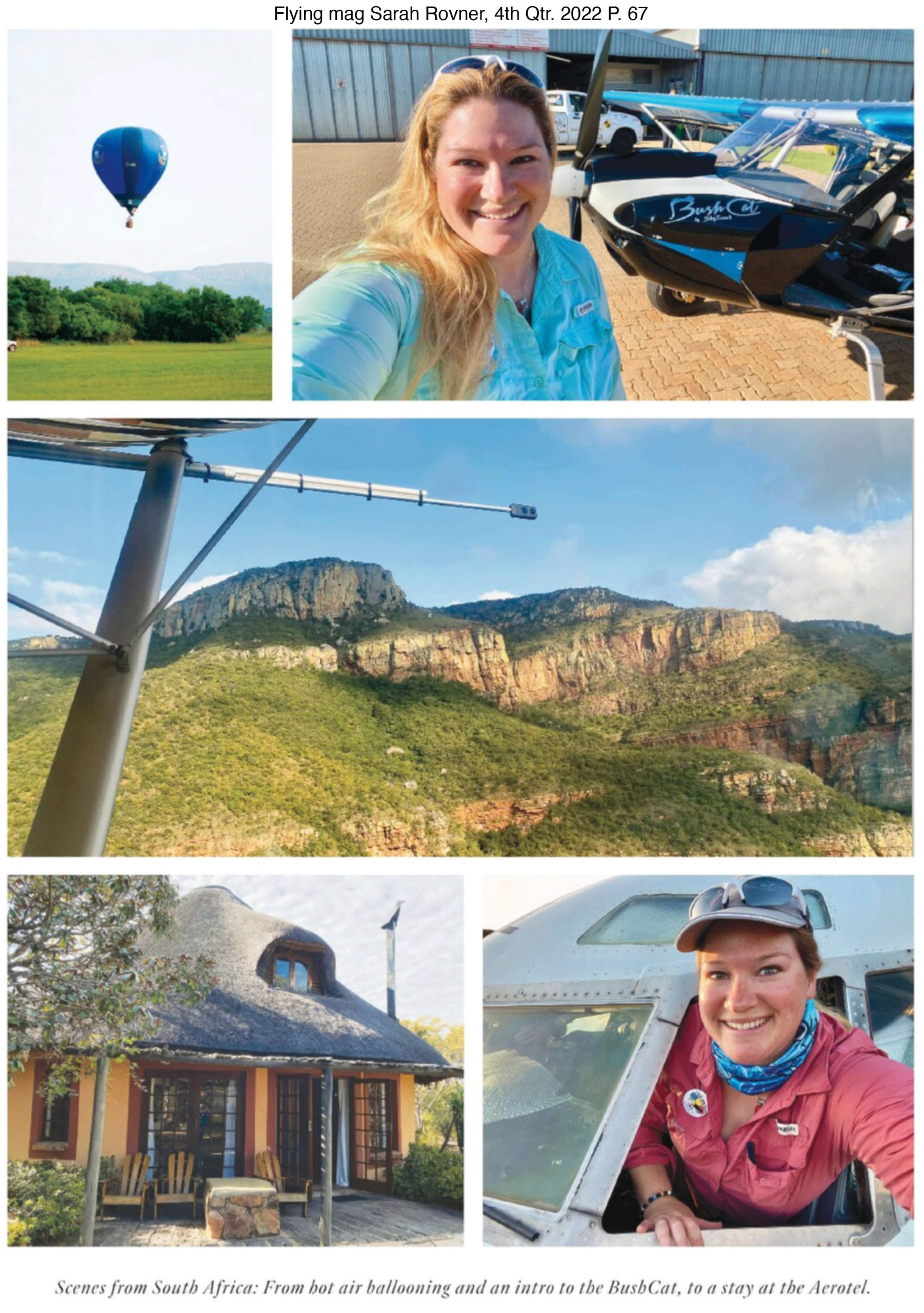

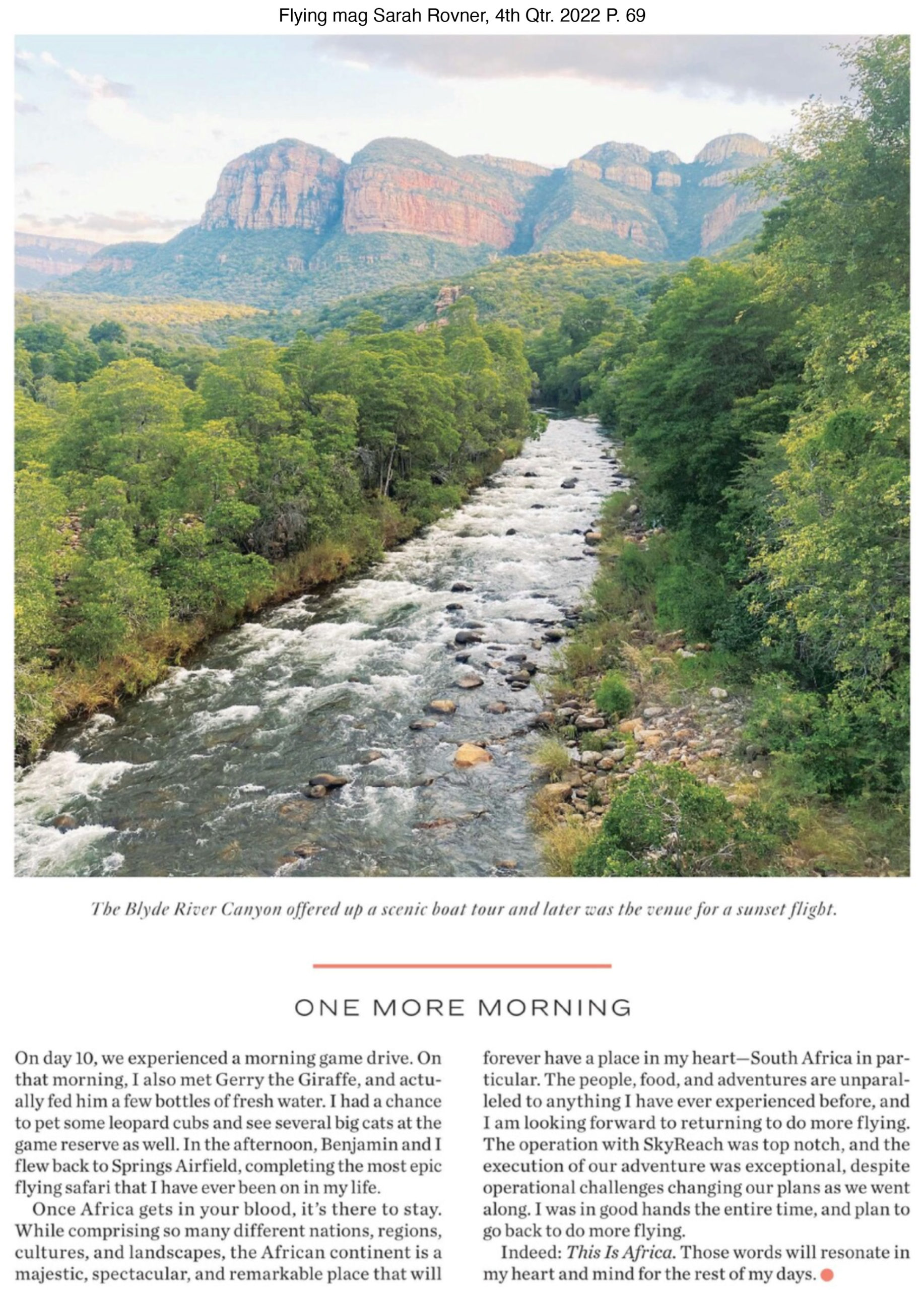

Story and images by Sarah Rovner – Flying magazine 4th Qtr. 2022

Sarah Rovner’s 1953 Piper PA-18-105 N148T “Patches” was chosen the 2021 PAAS President’s Award by the Potomac Antique Aero Squadron, SEE: https://www.flickr.com/photos/massey_aero/51399535062/in/photolist-2mj143o-2mj62K9-2maikNG

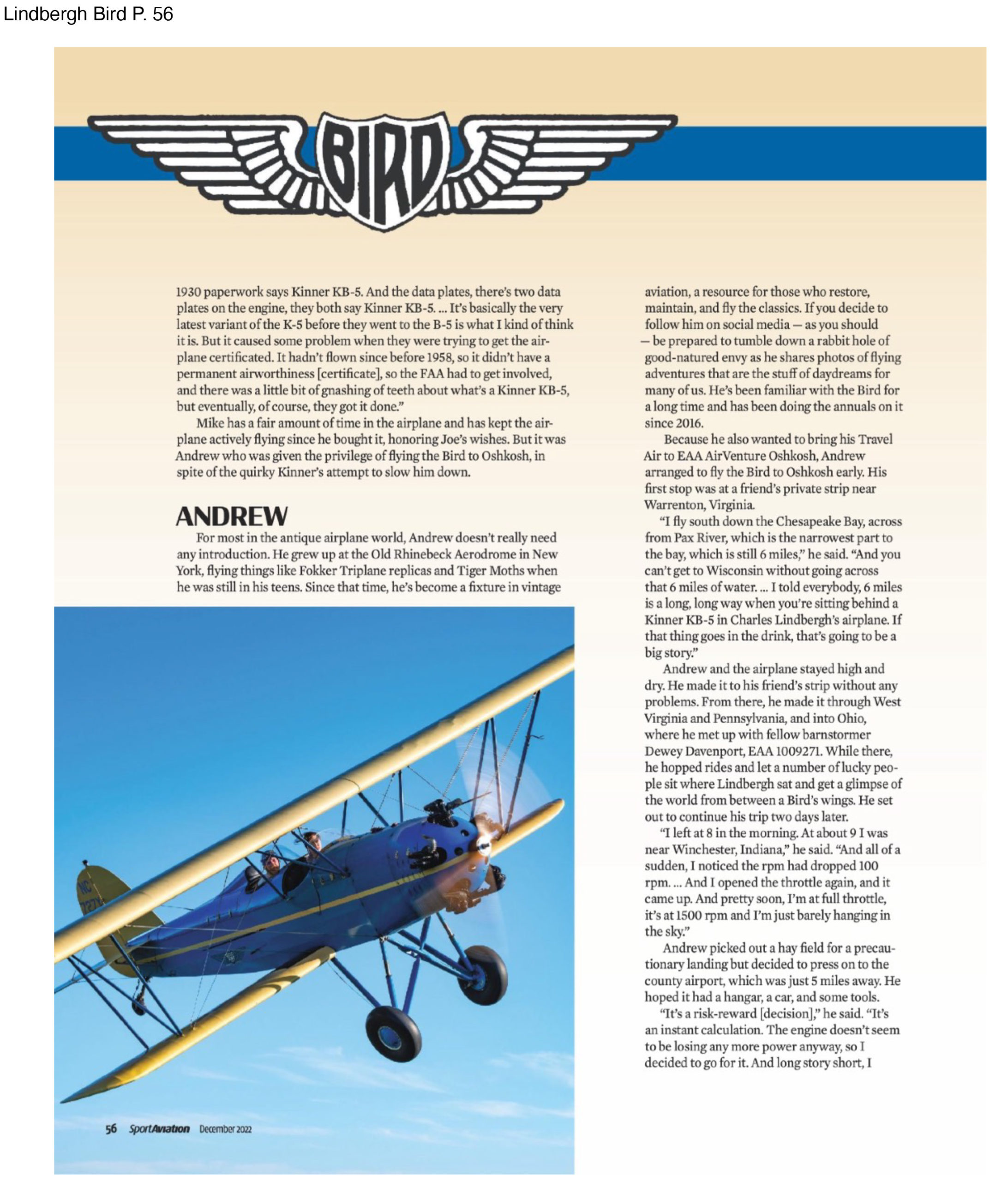

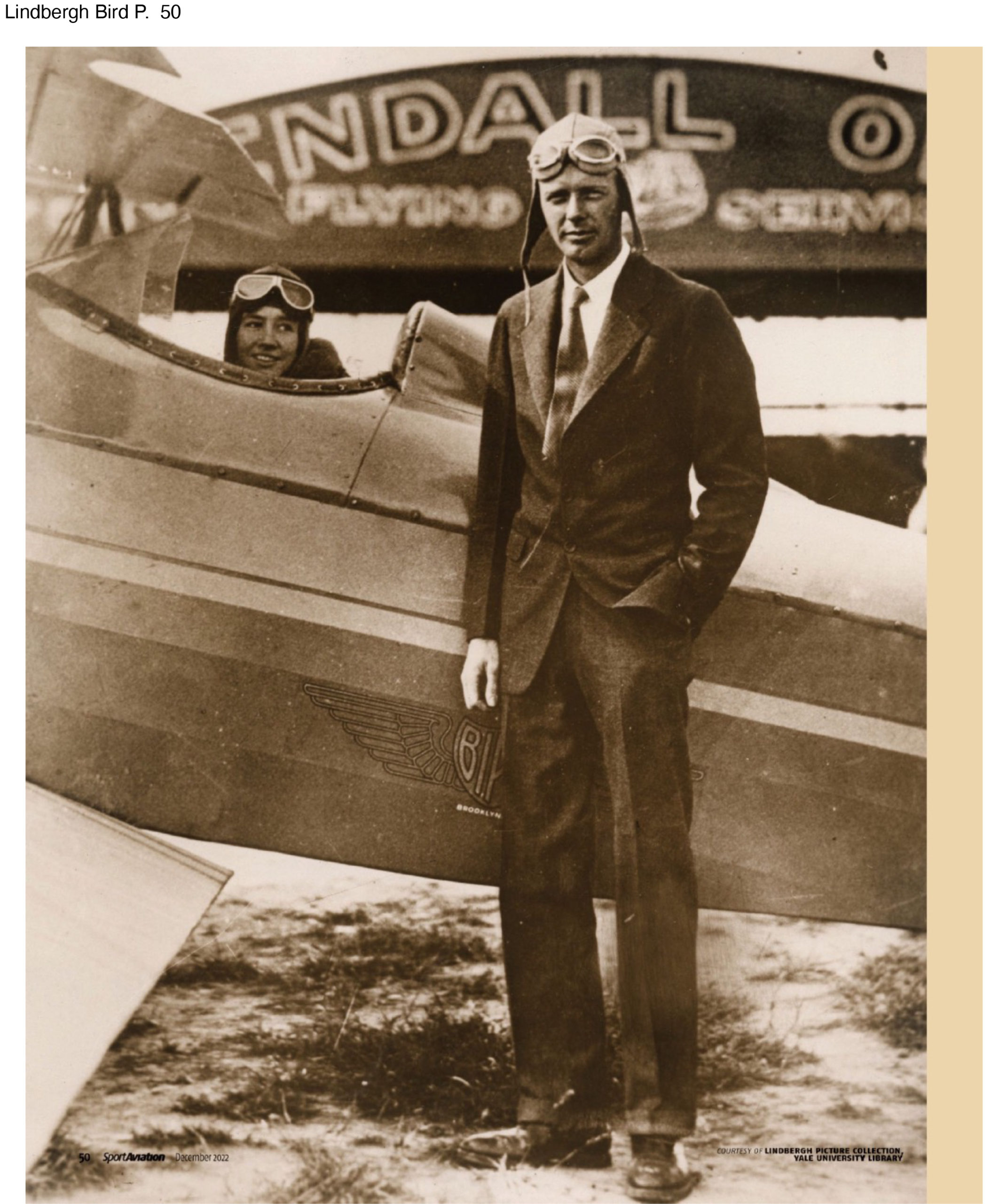

“A Lindbergh Legacy” Mike Pangia’s Brunner-Winkle Bird by Hal Bryan, Sport Aviation Dec. 2022

May 14 (Sat): 18th Chili Fiesta Fly-in

Fly in, Drive in, with your best chili recipe and/or covered dish, dessert item (optional). This annual event attracts local towns folk, and if weather permits, a large contingent of interesting flying machines. Festivities begin at 11 AM and go until 2 PM (Food Served at Noon). Renew old friendships and discover what everybody’s been working on all winter. General Public Invited! No Admission or Parking charge. The Airport & Museum are open, family friendly and handicap accessible (on grass). Antique and Show cars are invited for non-judged display (If you have a motorcycle, vintage car or hot rod, come early, park up front around the DC-3 for everyone to see & admire). It will have been 3 years since the 17th Chili Fest Fly-In – Boy time flies when you’re having fun, Huh!? I think we deserve really good weather, Don’t you?